Last month Libya’s National Oil Corporation (NOC) agreed for BP to start drilling for and producing natural gas in a major project off the coast of the north African country.

The UK corporation, on whose board sits former MI6 chief Sir John Sawers, controls exploration areas in Libya equivalent to nearly three times the size of Wales.

British officials have long sought to profit from oil in Libya, which contains 48 billion barrels of reserves – the largest oil resources in Africa, accounting for 3% of the world total.

BP is one of the few foreign oil and gas companies with exploration and production licences in Libya. Its assets there were nationalised by Muammar Gaddafi soon after he seized power in a 1969 coup that challenged the entire British position in the country and region.

After years of tensions between the two countries, prime minister Tony Blair met Gaddafi in 2004 and agreed the so-called ‘Deal in the Desert’ which included a $900m exploration and production agreement between BP and Libya’s NOC.

BP re-entered the country in 2007 but its operations were scuppered by the war of 2011 when British, French and US forces with the support of Qatar and Islamic militants overthrew Gaddafi.

Terrorism and civil war subsequently engulfed the country and oil company operations were put on hold.

The restart of BP’s operations follows the signing in 2018 of a memorandum of understanding with the NOC and Eni, the Italian oil major, to resume exploration, with Eni acting as the operator of the oil fields. BP chief executive Bob Dudley hailed the deal as an important step “towards returning to our work in Libya”.

The BP-ENI project, an $8bn investment, involves two exploration areas in the onshore Ghadames basin and one in the offshore Sirte basin, covering a total area of around 54,000 km2. The Sirte basin concession alone covers an area larger than the size of Belgium.

The UK’s other oil major, Shell, is also “preparing to return as a major player” in Libya, the company has stated in a confidential document. After putting its Libyan operations on hold in 2012, the corporation is now planning to explore for new oil and gas fields in several blocks.

Oil bribery

A third British company, Petrofac – which provides engineering services to oil operations – secured a $100m contract in September last year to help develop an oil field known as Erawin in Libya’s deep southwest.

Petrofac was at the time under investigation for bribery by the UK’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO).

One of its executives, global head of sales David Lufkin, had already pleaded guilty in 2019 to 11 counts of bribery.

The month following the award of the Libya contract, the SFO convicted and fined Petrofac on seven counts of bribery between 2011 and 2017. Petrofac pleaded guilty to its senior executives using agents to bribe officials to the tune of £32m to win oil contracts in Iraq, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

“A key feature of the case”, the SFO noted, “was the complex and deliberately opaque methods used by these senior executives to pay agents across borders, disguising payments through sub-contractors, creating fake contracts for fictitious services and, in some cases, passing bribes through more than one agent and one country, to disguise their actions”.

Petrofac works with BP in several countries around the world, including Iraq, Azerbaijan and Oman and in the North Sea.

Government backing

All three British companies re-entering Libya have strong links to the UK government. In some of the years during which Petrofac was paying bribes, the company was led by Ayman Asfari, who with his wife donated almost £800,000 to the Conservative Party between 2009 and 2017.

In 2014, Asfari, who is now a non-executive director of Petrofac, had been appointed by David Cameron to be one of his business ambassadors.

Petrofac, which is incorporated in the tax haven of Jersey, has also benefited from insurance provided by the UK taxpayer via UK Export Finance (UKEF).

“Petrofac was one of five companies sponsoring the official reopening of the British embassy in Tripoli”

In May 2019, when Petrofac was under investigation by the SFO, UKEF provided £700m in project insurance for the design and operation of an oil refinery at Duqm in the dictatorship of Oman, a project in which Petrofac was named as the sole UK exporter.

In June this year Petrofac was one of five companies sponsoring the official reopening of the British embassy in Tripoli. Ambassador Caroline Hurndall told the audience: “I am especially proud that British businesses are collaborating with Libyan companies and having a meaningful impact upon Libya’s economic development. Many of those businesses are represented here tonight”.

BP and Shell are especially close to Whitehall, with a long standing revolving door of personnel between the corporation and former senior civil servants.

Lobbying

Frank Baker, then the ambassador to Libya, wrote in 2018 that the UK was “helping to create a more permissible environment for trade and investment, and to uncover opportunities for British expertise to help Libya’s reconstruction”.

Since then, new ambassador Hurndall has held meetings with Libya’s oil minister, Mohammed Aoun, to discuss the return of UK oil companies to Libya, and the NOC has set up a hub in London, its only one outside Libya and the US.

The NOC’s London unit, launched in early 2021, is poised to “award consultancy and asset management contracts worth hundreds of millions of pounds over the next several years to British companies”, the Times reported.

Also heavily promoting British oil interests is the Libyan British Business Council (LBBC), whose president is Lord Trefgarne, a former minister under Margaret Thatcher, and which is chaired by former British ambassador to Libya, Peter Millett.

The LBBC, which sent a delegation to Libya earlier this month, says it acts “as an influential and informed advocacy group on behalf of UK business in Libya – in dialogue with the British government” and others.

In October 2018, the LBBC and the NOC signed a ‘statement of intent’ on the subject of “enhanced cooperation in the development of Libya’s oil and gas industry”. It also called for “mutually satisfactory contracts”.

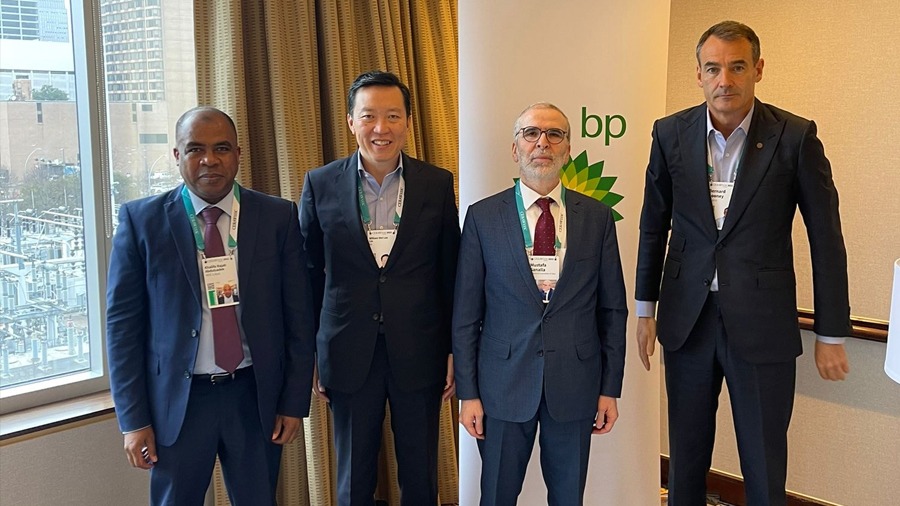

The chair of the NOC, Mustafa Sanalla, said at the time that “the UK is a key partner for Libya in boosting oil production” and welcomed “strengthening this partnership”. The LBBC pledged to “facilitate Chairman Mustafa Sanalla’s access to British government ministers”.

Control of oil

Last year, Libya was the UK’s third largest source of oil, after Norway and the US, supplying 7.8% of all British oil imports. Oil is Libya’s lifeline, providing over 90% of the country’s revenues.

But the country’s civil war has provoked a battle for control over the oil industry which has been described as being in “disarray”, with “little clarity on who really is in control of the nation’s most valuable resource”. The UN-backed Government of National Unity, which is supported by the UK, sits in the capital, Tripoli, while in the east of the country sits a rival government.

Most of Libya’s oil fields are in the east, which is controlled by commander Khalifa Haftar and his Libyan National Army allied to the eastern government.

In the international rivalry over accessing Libya’s oil, UK ministers have long tried to get British hands on the key resource. Documents uncovered by oil-focused NGO, Platform, in 2009 showed Labour ministers and senior civil servants met Shell to discuss the company’s oil interests in Libya on at least 11 occasions and perhaps as many as 26 times in less than four years.

Shell was one of the first western oil companies to re-enter Libya after the end of United Nations sanctions and a commitment from Gaddafi to stop funding terrorism and pursuing nuclear weapons.

Fuelling rebels

The 2011 war did not stop the UK pursuing its oil interests. During the early months of the uprising against Gaddafi, British oil trading company Vitol provided rebels with refined petrol in exchange for future delivery of crude oil, thus sustaining their military activities.

Those rebels, which included hardline Islamist forces, were being heavily armed by Qatar with British support. The deal with Vitol was masterminded by Alan Duncan, the former oil trader turned UK foreign minister, who has close business links to the oil firm and subsequently took a paid position with the corporation.

When during 2014 to 2016 and in early 2020 Libyan warlords such as Haftar shut down the Libyan oil industry, Vitol also helped to import refined products.

Once again, UK oil interests look set to be accompanied by a resurgence in the British military presence in Libya. In September this year the UK’s senior military official in the Middle East, Air Marshal Martin Sampson, discussed military training programmes with Libyan prime minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah.

The meeting followed the docking in Tripoli of UK Royal Navy warship HMS Albion, for the first time in eight years. Around a hundred Libyan and foreign dignitaries were hosted aboard Albion, including “senior Libyan political, military, and civil society figures”, the Royal Navy said.