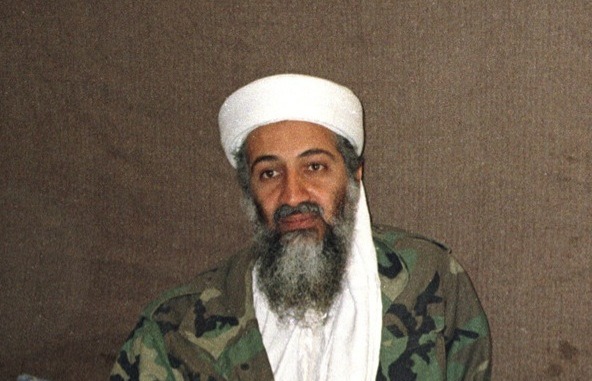

When Osama Bin Laden fled Afghanistan after 9/11, an old friend helped him escape the US manhunt. Yunus Khales, the veteran commander of Afghan mujahideen group Hezbi Islami (Islamic Party), had long supported Al Qaeda’s leader.

In 1996, when Bin Laden was expelled from Sudan, it was Khales who welcomed him to Afghanistan, giving him a house and land near the eastern city of Jalalabad. The site was a couple of hours drive from the Tora Bora mountains, which would become Al Qaeda’s headquarters.

Some say Khales was effectively a father figure to Bin Laden. A former head of the CIA’s Bin Laden unit has said: “Osama lost his father when he was young, and Khales became a substitute father figure to him. As far as Khales was concerned, he considered Osama the perfect Islamic youth.”

The bond between these two men is especially embarrassing for Western governments. Khales was invited to the White House in 1987 where President Reagan called him a hero for fighting against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

Similarly, the British authorities paid for Khales to fly to London in February 1987 in an attempt to charm the mujahideen leader. Around the same time, Khales’ field commander Jalaluddin Haqqani was fighting alongside Osama Bin Laden at the infamous Battle of Jaji in Afghanistan.

The weeks-long battle in the eastern Paktia province pitted mujahideen armed with UK-supplied Blowpipe missiles against Soviet troops. Bin Laden, who had by then recruited dozens of Arab fighters, suffered a foot wound in the fighting. Al Qaeda was formed the following year.

While Khales was in the UK, his group claimed responsibility for shooting down an Afghan government plane, killing between 30 and 43 people on board. Khales said the dead were soldiers, but others say they were civilians, including women and children.

This attack on an airliner did not derail his stay in the UK, as British authorities were willing to overlook such incidents in order to support Afghans fighting against their shared enemy, communism.

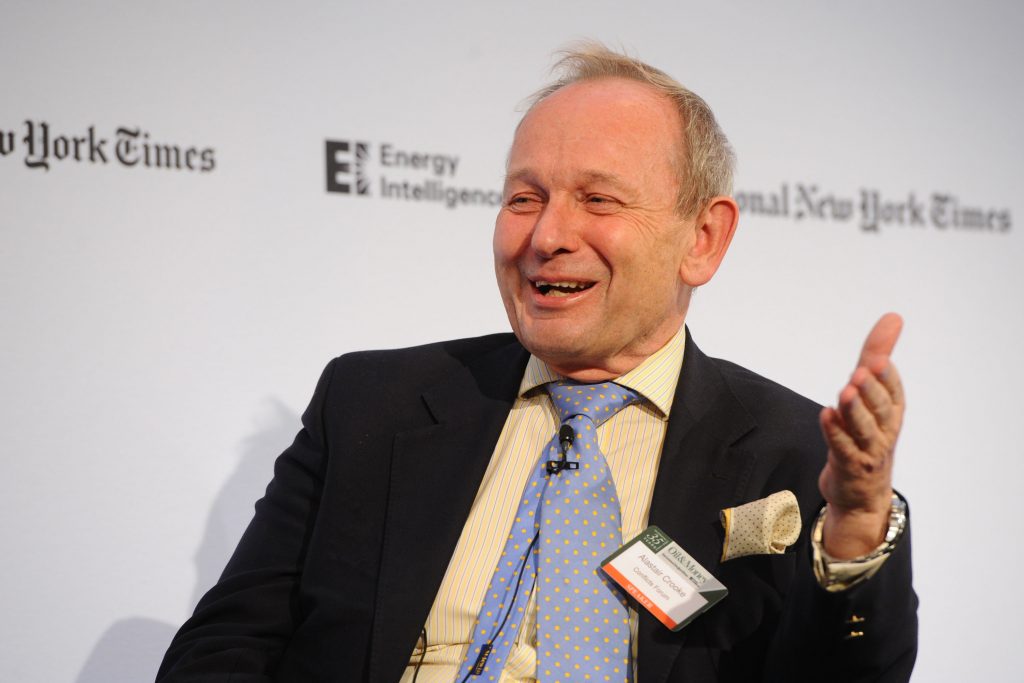

Although Khales’ visit to London was briefly reported in the press at the time, new details of his trip have emerged in formerly classified files at the UK National Archives. These papers reveal how an MI6 officer working out of the British Embassy in Pakistan, Alastair Crooke, played a pivotal role in arranging the visit.

MI6’s covert operation

Not only did Crooke refund Khales’ club class air fare, but the MI6 man even arranged for the mujahideen leader to receive medical treatment from Dr Anthony Rickards, one of London’s top cardiologists. Rickards was renowned for pioneering pacemakers, a lifesaving device which Britain’s Cabinet Office initially thought Khales might require.

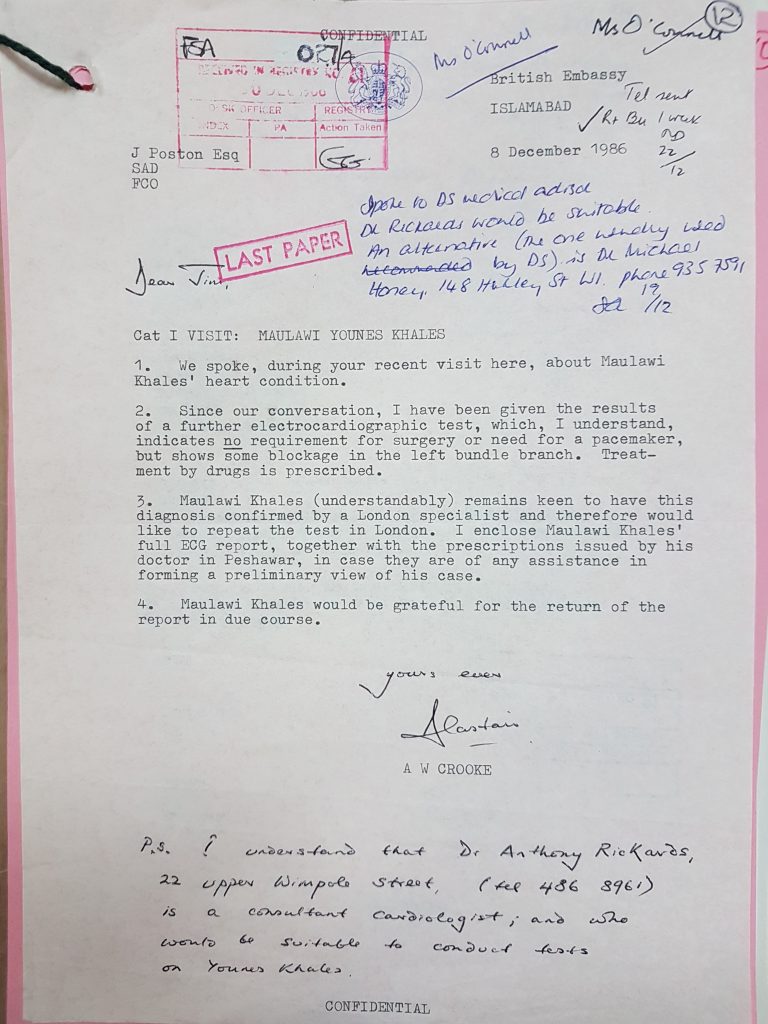

Crooke was close enough to Khales to have possession of his medical records. “I have been given the results of a further electrocardiographic test, which, I understand, indicates no requirement for surgery or need for a pacemaker, but shows some blockage in the left bundle branch,” Crooke informed his partners in the UK Foreign Office. “Treatment by drugs is prescribed.”

He added: “Khales (understandably) remains keen to have this diagnosis confirmed by a London specialist and therefore would like to repeat the test in London. I enclose Maulawi Khales’ full ECG report, together with the prescriptions issued by his doctor in Peshawar, in case they are of any assistance in forming a preliminary view of his case. Maulawi Khales would be grateful for the return of the report in due course.”

Crooke, who referred to Khales as “Maulawi”, an honorific title for Islamic teachers, went on to specify that Dr Rickards “would be suitable to conduct tests” on him, enclosing the consultant cardiologist’s phone number and address – a clinic 100 metres away from Harley Street, the centre of London’s private healthcare sector.

Following representations by Crooke and Britain’s ambassador to Pakistan, Khales was booked in for an X-ray and ECG with Dr Rickards. While in London, Khales made several trips to see Dr Rickards, who told him that “his heart problem was not serious and no surgery was needed.”

Khales went on to live until 2006, passing away aged 87 while on the run from US forces. Dr Rickards died in 2004.

When contacted by telephone last week, Crooke did not deny MI6 had helped Khales receive medical treatment. But he refused to elaborate, telling Declassified: “I have to be very careful about talking about anything that has been classified so I’m not sure if I can speak to you.”

He said the Foreign Office: “periodically warns me off with threats of the Official Secrets Act and so I have to be very careful to try not to touch on things that involve classified information. The British government is still highly sensitive about Islam and terrorism now because of what happened in Afghanistan.”

He added: “In some ways they’re trying to stop declassification of the policies that were being pursued in those years. They still regard the policy issues as highly sensitive or damaging if they’re discussed in public.”

Crooke did not reply to a follow up email Declassified sent him asking more detailed questions.

‘A man of principle and courtesy’

Although MI6 has never formally declassified any of its records, Foreign Office files from 1987 shed some light on what Khales did in London, aside from seeking medical treatment.

The other aim of his visit was to “consult with Ministers, Officials and MPs about the prospects for Afghanistan, the Jehad, and political developments.” A UK government profile of Khales described him as a “bluff, no-nonsense man, with few pretensions and a sense of humour. A man of principle and courtesy.”

He was invited to Britain as a guest of the Foreign Office, who sent an escorting officer in a car to greet him at Heathrow. The plan was to put him up at Royal Horseguards, a luxury five star hotel in Whitehall. In the event, Khales arrived four nights early, forcing the British government to accommodate him for longer than anticipated.

Michael Holman, the escorting officer, commented that Khales’ “arrival in Britain bordered on farce” and his “unusual appearance could not fail to excite attention. He appeared to suffer from a degree of ‘culture shock’ at the beginning of his visit and was grim-faced and unresponsive.”

After spending several days settling in and receiving medical treatment, Khales was driven to the School of Oriental and African Studies to meet its academic experts on Afghanistan before heading to the offices of the Economist, Independent, The Times and BBC for interviews.

He told the Independent that after a mujahideen victory “those people we know to be committed communists will be killed”. Although the Foreign Office felt this stance was “not helpful to the peace process” in Afghanistan, the diplomats took Khales for lunches at an Afghan restaurant in Paddington and the salubrious Cafe Royal on Regent Street.

He was also driven to parliament to watch Prime Minister’s Questions from the Strangers’ Gallery, where Conservative MP Viscount Cranborne had been primed to ask Margaret Thatcher if she was “aware of the visit this week to Britain of Maulawi Younes Khales, leader of the Hezb-i-Islami of Afghanistan.”

Cranborne, a fervent anti-communist, called on the prime minister to “reassert Her Majesty’s Government’s support for the right to self-determination for the people of Afghanistan, free of outside interference.”

Thatcher responded by declaring her wholehearted belief “in self-determination for the people of Afghanistan, and that the occupying forces of the Soviet Union should be withdrawn completely.”

Khales missed this moment as he had gone to pray. Later he met Cranborne in the central lobby and went to a committee room meeting with the Anglo-Afghanistan parliamentary group, where he met other supportive MPs such as Winston Churchill’s grandson.

‘Admire your resistance’

The highlight of Khales’ visit was reserved until the last day, when he met foreign minister Timothy Eggar. Briefing notes informed Eggar that there were seven Afghan resistance groups based in Peshawar, Pakistan, loosely bound together in an alliance. Three were “‘moderate’ parties based on the former aristocracy and spiritual leadership” and four were “‘fundamentalist’ parties deriving their support from the highly politicised and fundamentalist petit bourgeoisie.”

Khales’ Hezbi Islami was one of the four parties recognised as “fundamentalist”. The Foreign Office noted, however, that he “plays a relatively constructive role within the alliance” and could be peeled away from some of his rival hardline leaders.

Eggar was instructed to tell the Bin Laden ally that the UK “admire[s] your resistance” and advise him to raise the “international profile of resistance” by gaining “support of Islamic non-aligned and third world countries”.

“More needs to be done,” a British official told Eggar. “We should encourage a tour by [a] joint spokesman. We would welcome an alliance office in London.”

If asked about arms supplies, Eggar was instructed not to comment beyond saying Britain does “all we can to support your cause.” Five million pounds a year of British aid was going to support Afghan refugees, and surface-to-air missiles were supplied covertly.

Minutes from the meeting show Khales said: “Mujahedin morale was high…There would be a fight to the death against the Communist regime.” He was particularly keen to sound out British attitudes “towards a future Islamic Government of the people’s own choice” in Afghanistan.

An official commented: “He harped on about HMG’s possible attitude if the Mujahideen set up a government in liberated areas. He is no fool and was putting down a marker.”

British officials hoped Afghanistan’s former king might be returned to power, but Khales was against this plan, telling Eggar: “The resistance were concentrating on the Jihad rather than the question of who would emerge as future leader: through a jirga or elections someone would emerge in the traditional way in due course.”

“…He enjoyed a joke but was not the sort of person one would invite to a dinner party”

Despite this focus on jihad, Whitehall felt the Khales visit “was undoubtedly a success at a time when the Mujahidin needed some corrective exposure in the light of recent media controversy.”

Although the Soviet-backed regime in Kabul criticised the visit, the Foreign Office defended it on the grounds that “We maintain regular contact with leaders of the Afghan resistance, who represent a significant body of opinion in Afghanistan.”

In his memoirs, Sir Nicholas Barrington, who became Britain’s ambassador to Pakistan later in 1987, described Khales as a “plump, henna-haired…elderly mullah of the old school…He enjoyed a joke but was not the sort of person one would invite to a dinner party.”

Barrington noted that Khales’ deputy Jalaluddin Haqqani, “was reputed to be one of the most effective mujahideen commanders in the field. Haqqani and his sons continued to play a role in the country for many years after Khales died, graduating to attacks on the Americans rather than the Soviets.”

The Haqqani network was one of the major insurgent forces fighting the Nato-backed Afghan government. The network is now run by Jalaluddin’s son, Sirajuddin, who the new Taliban regime has appointed as its interior minister.

The Foreign Office and MI6 did not respond to a request for comment.