In May it emerged that Western war veterans were embroiled in mercenary plots from North Africa to South America. Five British mercenaries were offered up to $150,000 each by Russian-backed rebels to sabotage the UN-recognised government in Libya, according to a leaked dossier.

Meanwhile, in Venezuela, US mercenaries were paraded on television after being captured during a coup attempt. These are just the latest incidents in decades of scandals involving Western mercenaries, but the UK continues to have no effective anti-mercenary legislation on its statute book.

The reason is that UK governments have long championed British private mercenary companies and in so doing have prevented significant international action to halt their activities, as Declassified has discovered in previously secret government files from the 1980s.

British diplomats spent that decade “going along” with attempts at the United Nations to ban mercenaries, treating it as a “public relations exercise vis a vis the Third World”, according to Foreign Office files, with little intention of signing any eventual international convention.

Margaret Thatcher’s government repeatedly considered “killing” the UN talks or letting them “ramble on” to indefinitely delay having to take action domestically against private armies, the files detail.

Throughout the 1980s, Britain’s delegation lobbied the UN not to adopt any definition of “mercenaries” that could include the Gurkhas – Nepalese soldiers who made up 10% of Britain’s infantry at that time – despite senior UK military and diplomatic figures referring to them in such language privately.

UK representatives were also under instruction to “resist any suggestion” that governments should prevent their citizens from going abroad to become foreign fighters.

Amid the talks, a concerned arms industry executive was personally reassured by the Foreign Office that any proposals put forward at the UN would not affect his business plans in the Middle East.

When the UN eventually drew up a treaty against mercenaries in 1989, the text contained multiple caveats which protected the Gurkhas.

Britain’s top diplomat at the UN regarded it as an “acceptable text” for Western countries to sign and would only hinder mercenaries involved in “nefarious activities such as a coup”.

But even with this watered-down definition, three ministers in Thatcher’s cabinet, who were tasked with considering whether to endorse the treaty, appear to have vetoed such a move.

The treaty has never been signed by the UK and documents that could contain the ministers’ political assessments of the treaty remain classified by the Foreign Office three decades later, preventing the public from knowing exactly why the trio decided not to support the ban.

One of the three politicians who was tasked with making the decision, the then-armed forces minister Archibald Hamilton, became a director of a British private security company months after leaving government.

Hamilton sat on the four-man board of Saladin Holdings Limited from 1993 to 1997 alongside its main partner David Walker, one of Britain’s most notorious mercenaries.

Walker was accused in the US Congress of orchestrating the bombing of a hospital in Nicaragua during the Contra invasion in the 1980s and has been linked to civilian massacres in Sri Lanka while running Saladin’s predecessor company, Keenie Meenie Services (KMS) Ltd.

Walker, a former Special Air Service (SAS) major now aged 78 and registered to an address in London, has never been prosecuted for any of his mercenary operations.

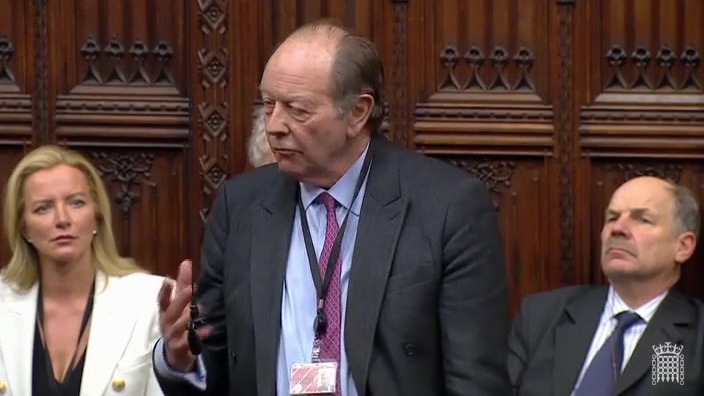

Hamilton now sits in the House of Lords, where he speaks in favour of the private security industry. He did not respond to our request for comment.

A Foreign Office spokesman refused to tell Declassified why some of its files remained sealed, only commenting that: “It is our longstanding position that this UN convention would not provide a workable basis for regulation under UK law.”

However, Dr Sorcha MacLeod, a member of the UN Working Group on the use of mercenaries, told Declassified: “Given the increasing use of mercenaries in numerous armed conflicts around the world, it is more urgent than ever that states protect human rights and support this international framework outlawing the use of mercenaries.”

‘Going along’

Declassified has analysed a decade of British government documents at the National Archives in London, detailing the Thatcher government’s extraordinary attempts to neuter a UN ban on mercenaries.

Her election as UK’s prime minister in 1979 came at a time when several African countries were demanding action to stop a repeat of British mercenary operations such as those led by “Mad Mike” Hoare in the Congo and Colonel Callan in Angola, which sought to profit from war.

Nigeria launched an initiative at the UN to draw up an international treaty against the recruitment, use, financing and training of mercenaries. Britain, which had no effective domestic laws against mercenaries, opted to participate in the UN discussions partly as “a justification for postponing national legislation”.

The UK’s outgoing Labour government had in 1979 considered making the recruitment of mercenaries a criminal offence, but Thatcher’s Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington decided to put the proposal “on ice” for two years upon entering office.

This temporary postponement turned out to be far more permanent. Over the next decade, the British Foreign Office privately planned to “go along with the idea of prohibiting recruitment of mercenaries” during UN talks while lobbying hard to ensure Britain’s own use of foreign soldiers was not curtailed.

Declassified files reveal that as early as 1981 British diplomats at the UN were under instruction to “resist any suggestion that a state should prevent the departure of its nationals from its territory on the suspicion that they intended to enlist overseas”.

British negotiators were also told to “insist on a definition of ‘mercenary’ which would exclude loan service personnel, contract personnel, Gurkhas, or other cases of legitimate services with the regular armed forces of a foreign state”.

As one Ministry of Defence (MOD) official explained starkly: “Our main interest in the discussion on mercenaries lies in our desire to avoid any definition of the term ‘mercenaries’ which might include our loan service and contract personnel and Gurkhas.”

At that time, there were hundreds of British officers on loan or on consultancy contracts to foreign militaries, particularly in those of key Middle Eastern allies. Moreover, around 10% of the British army’s infantry strength was provided by Gurkhas, who were recruited from Nepal.

Privately, the declassified files cite several senior British military and diplomatic figures accepting that the Gurkhas were mercenaries, in direct contradiction to their stance at the UN negotiating table.

For example, Lieutenant-Colonel Kenneth Grapes wrote in 1980 as part of a MOD study of the Gurkhas: “The principal reason for their serving as mercenaries is to save sufficient money to return to Nepal at the end of their service with improved financial status for their families and other dependents.” (Emphasis added.)

Reassuring the arms industry

Britain participated in the UN process of drafting an international ban throughout the 1980s, although Foreign Office ministers “thought it highly unlikely that the present Government would ever wish to promote legislation on Mercenaries or that there would be adequate support for such a move amongst their supporters in Parliament”.

The mixed messages did cause some confusion, and at one point a British diplomat had to reassure a major arms company that its activities were not likely to be impeded by any new treaty at the UN.

Thatcher’s government operated a state-owned arms dealer, International Military Services (IMS), which was, in 1984, “contemplating enlarging their recruitment of personnel to work in a supportive role with foreign armed forces”.

IMS’ counsellor for Middle East business, Alec Ibbott, was “concerned that such personnel might be considered as mercenaries”.

In response, a British diplomat in the Foreign Office’s United Nations Department “sought to assure” Ibbott that the IMS plan “did not fall foul” of any current international restrictions on mercenaries, and briefed him on background about the status of negotiations at the UN.

Later in the 1980s, the Foreign Office would make another display of support on behalf of British military contractors.

Whitehall reminded overseas posts that the MOD’s Defence Export Services Organisation (DESO) was “naturally anxious to support the activities of reputable British companies” who provided military training and advice to foreign governments “often in conjunction with, or in support of, the sale of British defence equipment”.

The activities of such companies were regarded as desirable “wherever these are compatible with the UK’s political, economic and strategic interests”.

‘Killing the whole exercise’

In 1985, British diplomats reviewed their UN negotiating strategy and identified three options. Firstly, to let the drafting committee “ramble on” for longer, which had “the merit of putting off the day when we might be required to think seriously whether or not the UK could go along with a Mercenaries Convention”.

The second option was “to try to make more constructive use of next year’s session of the Committee” to find a mutually agreeable treaty.

The third proposal was “to look for ways of killing the whole exercise”, such as passing a legally non-binding “declaration” about mercenaries rather than a treaty.

As it turned out, negotiations continued into 1986, by which point the activities of British security contractors were beginning to complicate efforts at the UN.

Amnesty International was criticising the work of Defence Systems Limited (now part of G4S), which was training Uganda’s security forces.

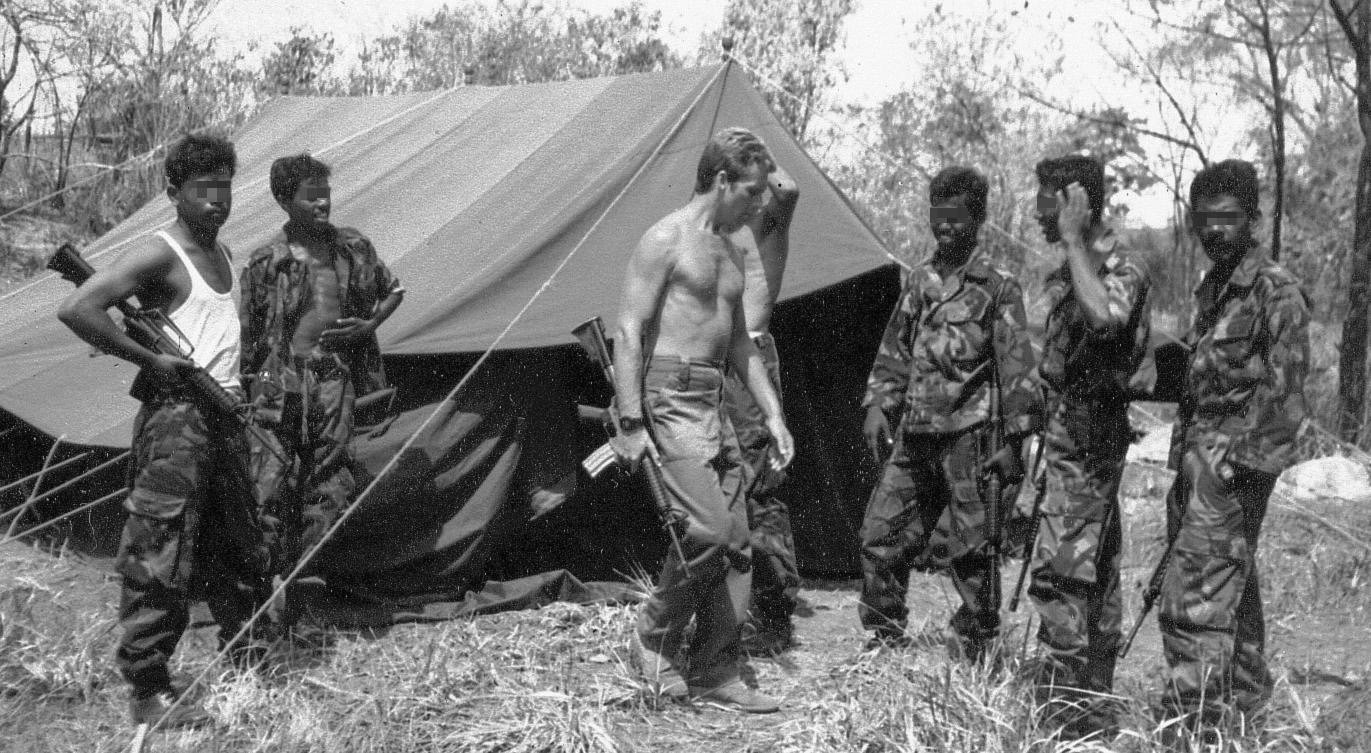

Another British company, KMS, was supplying helicopter gunship pilots for Sri Lanka’s air force. The pilots were implicated in massacres of Tamil civilians, such as in the farming village of Piramanthanaru on 2 October 1985 when 16 unarmed people were killed.

Opinions varied on how to handle firms involved in such operations. Britain’s export controls did not restrict the provision of military training and the Foreign Office noted that ministers could introduce a new law requiring UK companies to obtain a licence to teach military tactics abroad.

Such licences could then be revoked if the company offered training “of a kind which we thought incompatible with the national interest,” one diplomat, Paul Lever, wrote.

However, he doubted the effectiveness of such a scheme, noting that British diplomats “can already make informal representations” to the “more respectable firms”. In the case of “the less respectable outfits”, such a licensing scheme in the UK “would probably simply cause them to establish themselves in Liechtenstein or Liberia”.

Concerns over British mercenaries led a UK government lawyer to repeatedly advise Whitehall that the only power available to ministers to stop KMS was to suspend the passports of its staff, which would prevent mercenaries from being able to leave the UK to work in Sri Lanka.

Crucially, this recommendation directly contradicted the instructions given to British diplomats at the UN negotiations, who were under orders to “resist any suggestion that a State should prevent the departure of its nationals from its territory on the suspicion that they intended to enlist overseas”.

Instead, the British government preferred to take the more “informal” approach to dealing with KMS, and the former vice-chairman of the Conservative Party, Sir Anthony Royle (Lord Fanshawe), was repeatedly asked in the mid-1980s to have private words with Colonel Jim Johnson, the head of KMS.

The two men were close friends. Johnson had been best man at Fanshawe’s wedding.

This use of the back channels had little impact on KMS helicopter operations in Sri Lanka and in 1987 the Foreign Office reflected that “irreputable [sic] activities by such companies [were] damaging our position on the subject of mercenaries at UN”.

By this time, KMS operations in another part of the world were also coming to light. In March 1987, the US Congress heard testimony that KMS director David Walker had worked with Oliver North and the Contras in their bid to overthrow Nicaragua’s democratically elected Sandinista government.

Walker was specifically implicated in the bombing of a hospital in the capital, Managua, but he has never faced charges in the UK for his work with KMS.

Endgame

By the late 1980s, Whitehall’s contempt for the UN negotiations was becoming more entrenched.

David Edwards, a Foreign Officer legal adviser at the UK mission in New York, said the chairman of the UN committee, Werner Vreedzaam from Suriname, was “not bright (to say the least) and when he does understand what is happening he is not helpful to Western positions”.

Edwards added: “Having said all this, however, I doubt whether it matters all that much, given our own attitude to this exercise. But it does give rise to a great deal of frustration amongst the better delegations.”

His colleagues expressed similar attitudes, especially towards attempts to set up a UN Special Rapporteur on Mercenaries, a new post that many UK officials opposed. In a handwritten comment, one British official scrawled “This is an exercise with great potential for anti-Western propaganda…my candidate would be ‘no-one’.”

A British government legal counsellor, Paul Fifoot, agreed, writing: “I have no candidates. An African would be totally unsuitable.” At a push, Fifoot appeared to countenance “A moderate Asian or W. European” taking up the role of Special Rapporteur.

Ultimately, the role was created and went to Senator Enrique Bernales Ballesteros from Peru, who wrote enthusiastically to Britain’s Foreign Secretary saying the UN convention under negotiation was “an instrument of the greatest importance in preventing and defending all States against mercenary attacks”.

Meanwhile, Edwards continued his cynical approach to UN efforts to outlaw mercenaries. “It might be wise… without actually taking the initiative, to watch out for opportunities to bring matters to a close,” he argued in January 1988. “It is therefore important now for Western countries to search for acceptable means for winding up the exercise.”

Although Edwards resented how long the proceedings were taking, he personally lobbied for delays when British interests were threatened. For example, attempts to reduce duplication of clauses that exempted the Gurkhas were resisted, with Edwards trying to “stall” the UN to secure “an element of belt and braces for the Gurkhas”.

As the UN debate on mercenaries entered 1989, now active for 10 years, the Foreign Office legal advisers drew up their endgame strategy. British aims included encouraging “any moves by other delegations to bring the matter to an early end”.

By then, the mask was beginning to slip, with British officials admitting privately that their participation in the UN debates over mercenaries was “to some extent a public relations exercise vis a vis the Third World. Although we deplore the use of mercenaries and say so publicly, we must, in these negotiations, be careful not to give any commitment that we will become party to a convention on this subject”.

Once again, as they had proposed in 1985, it was better the UN efforts were watered down to a non-binding declaration.

“It would be wise … to watch out for opportunities to kill the matter, such as other States suggesting the making of a declaration instead of a convention,” the British government’s legal advisers strategised.

‘An acceptable text’

Despite these desires to sabotage the proceedings, by the end of 1989 the UN group had finalised a draft treaty against mercenaries that one British official described as an “acceptable text” for Western countries to sign.

Sir Crispin Tickell, the most senior UK diplomat in New York, wrote to foreign minister Tim Sainsbury MP recommending that Britain support the treaty. He explained reassuringly that it defined mercenaries “in such a way as to exclude the Gurkhas and the French Foreign Legion”.

The only people who would be affected by the treaty were “ex-members of foreign armed forces who are recruited for nefarious activities such as a coup” and “there would be no safe haven for mercenaries or their paymasters.”

Sir Crispin continued to press his argument, saying: “At the moment no mercenary activities can be controlled under our existing law. It does not do us any good to say that we deplore mercenary activities, but plead inadequacy of our domestic law.”

Days before Christmas 1989, the Foreign Office commented privately: “The next stage is to consider whether it is in our interest to sign” the Convention.

Alongside Sainsbury, two other ministers were asked to consider the matter, including Hamilton who would later become a director of Saladin Holdings Limited alongside notorious mercenary David Walker.

The UK never signed the convention, but the ministers’ reasons are not public. The subsequent file in this series is not available at the National Archives as it has been withheld by Foreign Office, which claims it was too sensitive to release three decades after it was written.

The UN convention against mercenaries was signed almost immediately by many African states as well as several European countries including Germany, Italy, Romania and Ukraine. By contrast, world powers such as Britain, France, the US, China and Russia have never endorsed the ban.

MacLeod, one of the UN’s leading experts on mercenaries, told Declassified more action is needed. “Currently a mere 36 states have ratified the Mercenary Convention and none of the permanent members of the UN Security Council has ratified it,” she said.

MacLeod noted how her UN Working Group on Mercenaries has “long urged all states to become a party to the International Convention”, which she felt was “imperative” for preventing the recruitment, use and financing of mercenaries.

An FCO spokesman told Declassified: “The UK has played a leading role in implementing international initiatives to effectively regulate private military and security companies, including as a founding signatory to the Montreux Document.”

The Montreux Document, which was signed in Switzerland in 2008, is exactly the type of non-binding declaration the British had privately been seeking in the 1980s. It was immediately criticised by campaigners who warned that it was not a substitute for legally-enforceable legislation.