A former British army general ran a war veterans’ charity while receiving tens of thousands of pounds in fees from the UK government to oversee welfare cuts that hit former soldiers, it can be revealed.

Lieutenant General Andrew Graham, who served in the UK military for three decades until 2011, was from 2013 chairman of Combat Stress, a charity supporting veterans with traumatic injuries, before standing down last month.

But in the year he joined the charity, he also became a member of the audit committee of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), the British government ministry responsible for welfare and benefit payments to people out of work or with disabilities.

Graham went on to sit on the board of the DWP which has been implementing severe cuts to the benefits budget, as part of the Conservative government’s austerity programme. From 2011 to 2018, the DWP experienced the second “most severe” budget cuts of any department, seeing its funding reduced by 41%, according to the think tank, the Institute for Government.

One of the charity’s ex-clients describes Graham’s role as “an appalling conflict of interest” and is demanding an inquiry.

Military veterans, many of whom have life-long mental illnesses or physical disabilities, are among the most reliant on Britain’s public services of any group, and have frequently criticised welfare cuts.

A survey by the Royal British Legion published in 2014 found that working-age veterans are more likely than the general population of the same age to be suffering from “a long-term illness that limits their activities”, including depression, hearing or sight loss, and musculo-skeletal problems.

A few months after Graham joined the DWP, 59-year-old unemployed ex-soldier David Clapson died when his job seeker’s allowance, the welfare benefit for the unemployed, was stopped. Clapson was diabetic and relied on a supply of refrigerated insulin. He had £3.44 left in his bank account and had run out of electricity and food. His body was found lying next to a pile of CVs.

Instead of reversing its cuts to welfare, however, the government began to implement an even more controversial policy known as universal credit — a single welfare payment that is meant to streamline the benefits process.

However, the new system has been widely criticised for claimants going weeks without income support. Many veterans have suffered under universal credit, especially those with severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that leaves them unable to work.

In one case, a DWP worker allegedly told someone who was applying for benefits:

“To be honest, all you veterans that say you’ve got PTSD and everything, it’s just a crock of shit.”

Graham had a role in the launch of universal credit. According to the DWP’s annual report for 2014-15:

“In his audit committee role, Andrew Graham gave particular attention and support to the team responsible for the rollout of universal credit.”

In 2015, the DWP’s top civil servant, Sir Robert Devereux, thanked Graham for his first two years on the audit committee, especially for “supporting us successfully to introduce major reforms to pensions and welfare”.

Graham was even promoted to become a non-executive director of the DWP, where he was now required to monitor “operational issues, such as the operational/delivery implications of policy proposals”.

Graham was not an entirely impartial policy expert. In 2016, he unsuccessfully stood as a Conservative Party candidate for Police and Crime Commissioner in Dorset.

Personal gains

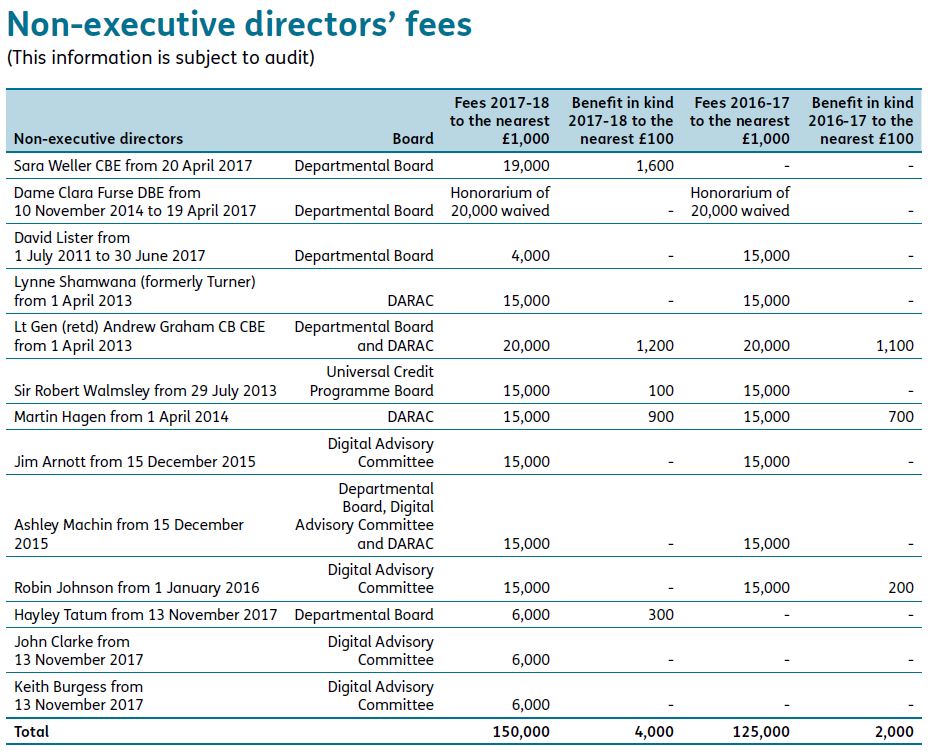

With Graham’s more powerful role in the DWP came some perks, including the ability to charge fees for any advice he provided. In his first year, he billed the DWP for just £1,000, according to official records, and attended one board meeting.

The following year, the general charged a lot more: £20,000, while receiving in-kind benefits worth £1,100. This made him the most expensive non-executive director on the DWP’s board, a pattern that was to continue.

For the year 2017-2018, Graham charged the DWP a further £20,000, plus benefits of £1,200, for attending nine meetings. In 2018-19, he charged the same amount again, meaning he has received at least £60,000 from the department over three years, while it has driven through some of its most severe cuts to the welfare budget.

In comparison, a single man aged over 25 is entitled to £317.82 a month living allowance if he receives universal credit, amounting to £3,813.84 a year.

The United Nations has criticised the DWP for its universal credit policy. In 2019, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty, Philip Alston, wrote in an official report after visiting Britain that he “heard countless stories of severe hardships suffered under UC [universal credit].”

He added: “These reports are corroborated by an increasing body of research that suggests UC is being implemented in ways that negatively impact claimants’ mental health, finances and work prospects.”

This February, the minister in charge of the DWP, Amber Rudd, admitted to Parliament that universal credit had increased food bank use because of delays in the benefits being paid.

Charity chairman

At around the same time he joined the DWP, Graham became chairman of Combat Stress, which describes itself as “the UK’s leading charity for veterans’ mental health”. Graham then oversaw a period of cutbacks at the charity, especially to its welfare services and residential treatment facility.

In 2013-14, the charity’s welfare officers were assessing 945 veterans while the organisation was spending £3.6-million on community and outreach services run by 64 staff, and providing veterans with a variety of guidance, including how to access benefits from the DWP.

By 2016, the charity announced a “review of our welfare service to reduce overlap with other organisations” and in January 2017, closed its entire “regional welfare service”, deciding to stop providing welfare support to veterans.

By 2018 — after five years of Graham as chairman — the charity’s annual spending on community services had fallen 25% to £2.7-million, which were now administered by only 49 staff.

The charity also took the decision to no longer deliver residential treatment at its Audley Court centre in Shropshire, and convert it into an outpatient centre instead. Audley Court was a key retreat helping veterans to deal with the often life-long condition of PTSD, earlier described by the charity’s clients as a “unique” service that was “like having a pair of arms thrown around us”.

Among those who went on residential retreats at Audley Court was Gus Hales, a former paratroop sergeant in the 1982 Falklands War who witnessed the bombing of the Sir Galahad warship, killing 48 servicemen.

In 2015, Hales’ support was suddenly withdrawn. A Combat Stress welfare officer came to his home in mid Wales and told him he was being discharged as a client. No precautions were taken to secure the help he needed for his PTSD and no care plan was provided.

Hunger strike

By 2018, Hales had become so distraught at being dropped by the charity that he went on hunger strike outside Audley Court in the run-up to Remembrance Sunday. He spent 18 days without food and had to be rushed to hospital.

Hales said the experience “nearly killed me”, but he succeeded in grabbing the attention of politicians, at least momentarily. The government’s veterans’ minister invited him to a meeting at the ministry of defence in London and pledged to “look into” his concerns. Combat Stress apologised for the way it had treated Hales and promised to conduct an internal review of what went wrong.

However, in October 2019, Hales was once again on hunger strike outside the Combat Stress office ahead of Remembrance Sunday, insisting not enough had changed. He says the charity’s review was never published and that veterans continue to go without the mental healthcare they need.

When shown evidence about General Graham, Hales told me:

“It is shocking to learn that the government had their man both inside the DWP and inside the charity Combat Stress.” He added: “This is an appalling conflict of interest and an official inquiry should start right now.”

Graham and Combat Stress did not respond to requests for comment. The Department for Work and Pensions declined to comment on Graham’s role, but said his tenure on the board ended in the summer.