“They hacked us to silence us,” shouts a man on a megaphone outside Kensington Olympia station in west London, where a giant inflatable effigy of a Gulf tyrant flutters in the autumn breeze.

Dressed in a white robe, chequered red head scarf and Stella McCartney sunglasses, Saudi dissident Yahya Assiri is protesting against a controversial Israeli tech firm, the NSO Group. It is taking part in the International Security Expo across the road in London’s Olympia, where thousands of securocrats are gathering for the annual two day event.

To gain access, the delegates – some of whom have spent £99 on tickets – must queue opposite Assiri and a row of Saudi human rights activists from the ALQST group, together with exiles from other Gulf countries and Amnesty International.

These protesters are angry at NSO Group for selling its highly sophisticated Pegasus spyware to Gulf regimes, which allegedly used it to hack their phones and uncover opposition networks – with devastating consequences.

“They arrested our contacts inside the country, they tortured them, they have been sexually harassed, so it’s not a joke,” Assiri says. Taking aim at the event organisers, Nineteen Group, he adds: “It’s something serious, and still you receive NSO here and you still close your eyes about their crimes.”

The fact NSO has been allowed to attend the event at all is a surprise. This summer saw a slew of allegations that its Pegasus product was used by autocratic regimes to hack hundreds of journalists and human rights activists around the world, and even broke into the French president’s phone.

Some British citizens who believed they were hacked have asked police to investigate NSO. Yet two months after the scandal broke, the company is exhibiting at an event endorsed by a senior Home Office minister, a chief constable and a Labour peer.

In fact, the NSO stand is in prime position just inside the entrance, where the company has set up a glitzy display that overshadows many of its rivals. I inspect the stall for any signs of Pegasus, but cannot see the product. Although the company says it never intended to exhibit the spyware in London, the protesters take credit for forcing the firm into a last minute climb down.

The only gadget NSO is exhibiting looks like a huge Wi-Fi router, perched on a tripod with two aerials sticking out. “Protect your skies,” says the branding, as an NSO representative happily tells me about their Eclipse technology which is designed to neutralise unwanted drones. UK airports are seen as a “big market”, especially after the Gatwick drone debacle of 2018.

When I ask NSO about Pegasus and the protest outside, staff signal for their colleague in PR, who has flown in from Israel especially for the event.

“Don’t believe everything you read,” she assures me from behind a black mask. If people are worried their phone has been hacked by Pegasus, the company can ask its customers to check whether certain mobile numbers have been infected, she insists.

‘In the wrong hands it becomes dangerous’

Photography is not generally allowed at the event, but I get to take away an NSO brochure which says the company provides technology to help governments and law enforcement in “preventing terrorism and crime”.

The problem is that in many Gulf countries, political parties are banned and free speech is illegal. ALQST’s website contains a disturbing database of prisoners of conscience in Saudi Arabia. Some of them, like Loujain al-Hathloul, are well known – she was locked up for demanding that women have the right to drive, and remains on an international travel ban.

But other names are not a cause célèbre in the West, despite having huge followings inside the Kingdom. Take Salman al-Odah, who has attracted 13 million followers on Twitter through his principled demands for reform. He faces the death penalty.

Or Hassan Farhan al-Maliki, an Islamic scholar critical of the state-sanctioned Wahhabi religious doctrine. He too faces execution.

It’s clear that regimes which are prepared to behead peaceful opponents, will have no qualms about using spyware like Pegasus to break into activists’ phones, even if they are living in exile. As the list of alleged victims grew during the summer, several were Bahraini activists or journalists in London who I knew or have worked with.

For ALQST, the issue is deeply personal, as its executive director Alaa Al-Siddiq is alleged to have been hacked by Pegasus. The 33-year-old died in a car crash in Oxfordshire shortly before the information emerged.

Although no foul play is suspected in her death, it marked the tragic end to a life of human rights activism, just months before her father Mohammed was due to be released from prison in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). He had been separated from her since 2012 for his political activism.

Such trauma and tragedy will not stop NSO from seeking to expand its footprint in the UK. In addition to the stand, its “client executive” Alexandra Syvan is among the speakers given a platform at the event.

A former Israeli military intelligence officer, she warns about the “high threat” posed by drones that can smuggle contraband into prisons, declaring that NSO’s Eclipse product can “protect borders or sensitive areas” with “no collateral damage”. Rather than using radio frequency jamming which can cause a drone to crash out of the sky, Eclipse performs a cyber attack to hijack its controls and pilot it safely to the ground.

Her presentation finishes sooner than expected, and I head for a stand run by the British government’s Department for International Trade. It has sent along staff from UK Defence and Security Exports, which is effectively a marketing agency for British arms dealers.

Based in Whitehall’s Old Admiralty Building, its 127 staff advise UK firms how to export their products, to all and sundry governments and regimes around the world. It performs its mandate well: In 2019, £11-billion worth of arms deals were signed by British companies, a value second only to the United States.

Pete Thompson, assistant head of its Cyber Exports Team, tells me UK tech firms are facing stiff competition from Israeli and French rivals. Most of the businesses he helps are selling what’s known as defensive cyber, like anti-virus software.

Asked if a British firm could face a similar scandal to the NSO group – selling offensive cyber hacking tools to repressive regimes – he points to a licensing regime that vets foreign customers.

“It can be something quite innocent but in the wrong hands it becomes dangerous,” he explains, setting out the human rights criteria that could prevent British surveillance equipment being used by autocrats.

Despite Thompson’s claims, it is already established that one of Britain’s biggest companies, BAE Systems, sold an advanced spying tool called Evident to regimes in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, Morocco and Algeria, where activists are comprehensively bugged.

‘Let’s have a debate’

Leaving Thompson to promote Global Britain, I continue round the exhibition hall, past stands full of padlocks, keys, CCTV, automatic bollards, grenade proof doors, sniffer dogs and walkie talkies. Eventually I reach a robotic helicopter.

This is the Revector stand, a British company with a 20-year history of detecting telecoms fraud. Its chief executive Andy Gent wants to tell me about his new product – a phone tracking device flown from a drone. Gent, a veteran of telecoms and internet ventures in Pakistan and Kuwait, is refreshingly upfront about his company’s use of technology that has been utilised across the world for years but has long been shrouded in secrecy.

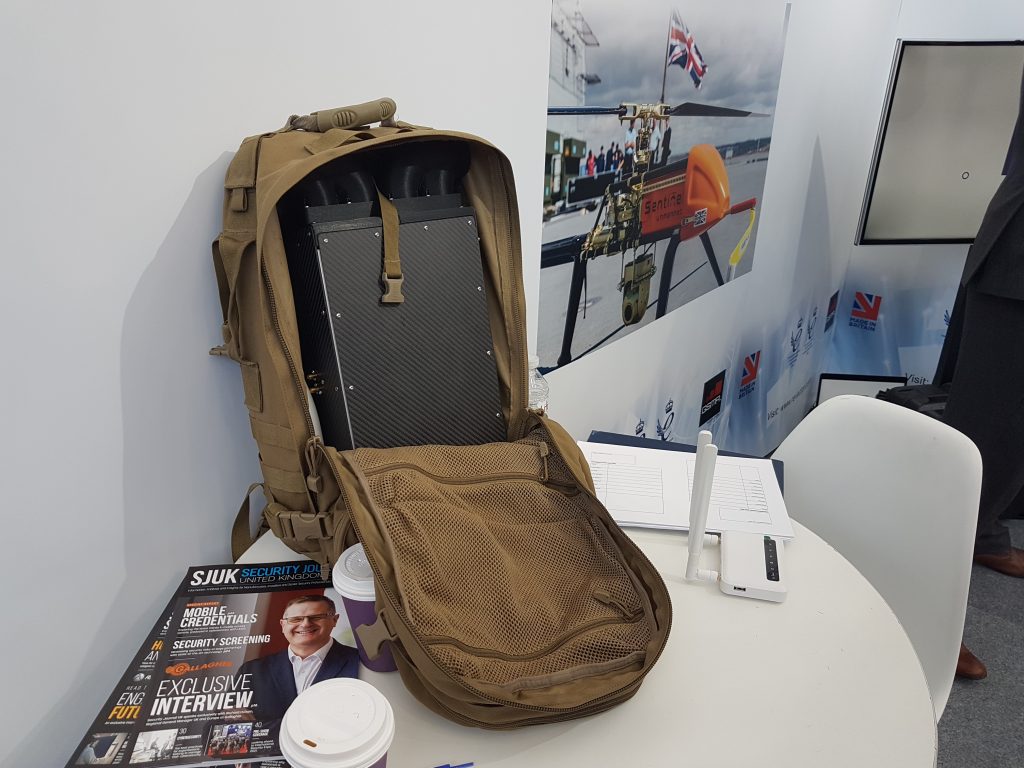

Every SIM card has an International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI), a numerical code assigned by phone companies to identify their customers. Gent is selling an IMSI-catcher, a black box the size of a small rucksack, which can quietly hoover up these codes allowing people to be tracked.

Privacy groups have long warned of the risks this technology poses, especially if police use them at political protests. “If I was allowed to turn it on here, I could catch everyone’s IMSI,” Gent explains, pointing to Olympia’s vast barrel-vaulted roof. But the law currently won’t let him use it in the UK, although seven British police forces are reported to have bought IMSI catchers.

Gent does not know who sold them those machines, and is unsure whether British police are using the devices or not. Instead he focuses on exporting his devices to countries where the systems are allowed – such as Honduras and “an African country” where they are used to detect fraudsters.

He believes it has other uses too – particularly for search and rescue in humanitarian disasters, where someone’s phone signal might stick out from an avalanche in the Swiss alps or an earthquake in Haiti. By deploying an IMSI-catcher from a drone, he says pilots will not have to risk flying helicopters into difficult and dangerous conditions.

Gent recognises the risks of selling such equipment abroad. “There’s a human rights issue – a government could switch what it’s being used for and go and locate people. If someone from Iran contacted us, we wouldn’t get an export licence.”

When asked whether he would sell such equipment to Iran if it was legal, Gent responded: “How you use it has got to be controlled. Let’s have a debate. I’m not going to take a moral ground on this. I’m running a company and a business. I always refer to the export authority. You’ve got to follow their rules.”

“If someone from Iran contacted us, we wouldn’t get an export licence.”

– Andy Gent, Revector

But the rules are not always a sufficient safeguard. In 2012, foreign minister David Lidington allowed a British firm, Gamma International, to sell an IMSI-catcher to police and intelligence agencies in Macedonia, where it was used to illegally wiretap thousands of activists, politicians, and journalists.

Hired muscle

After meeting Gent, I head for a cluster of private security companies. One of them is Pilgrims, which takes its name from a poem popular in the SAS and mostly employs special forces veterans. A manager, Phil Drinkwater, talks me through the hostile environment training it provides to journalists who are headed for war zones.

Drinkwater served as a British army officer in Helmand province, Afghanistan, and says Pilgrims has managed to keep a toehold in the country despite the Taliban takeover, mostly providing security for Western media, although his team had to turn over their weapons.

We speculate on what approach the Taliban might take towards private security, an industry that boomed during the US occupation. Turkey and Qatar are trying to land a deal to provide security at Kabul airport, suggesting the new Taliban regime is not ideologically opposed to the concept of private military contractors.

Whatever happens in Afghanistan, Pilgrims has its fingers in plenty of other pies. It has a £5-million contract to guard British diplomats in Nigeria and neighbouring countries. In fact, the west African region has become so unstable Pilgrims has to provide a “quick reaction force”. For a number of years, it also helped the Home Office to deport asylum seekers to Yemen and Somalia.

Next to the Pilgrims’ table is GardaWorld, a much larger Canadian company which was poised to buy up G4S before pulling out of the takeover bid in February. It already has deals with the Foreign Office to guard embassies in Iraq, Libya, Somalia and until recently Afghanistan. Together these government contracts alone were worth nearly £100 million.

Despite receiving so much in public funds, GardaWorld has largely avoided G4S-style controversies. This changed briefly during the recent evacuation of Kabul, when it emerged that GardaWorld’s 125-strong Afghan staff guarding the British embassy would not be eligible for asylum in the UK. The furore forced the government into an embarrassing U-turn.

But, although GardaWorld has had to pull out of Afghanistan for now, its staff at the Olympia seemed bullish about a return if the conditions allow. A fresh faced company rep told me: “High risk environments like that are a huge opportunity for us.”