Sixteen people were killed by rubber or plastic bullets during the Troubles (a seventeenth was killed by a fall after being hit by a bullet). Some victims had been involved in street disorder but others were passers-by.

Eight of the dead were children under 16. None was armed.

Rubber and plastic bullets have never been deployed in England, Scotland or Wales, whereas over 120,000 such rounds were fired during the three decades of conflict (1968-1998) in Northern Ireland.

British soldiers killed 11 people while police from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) killed six.

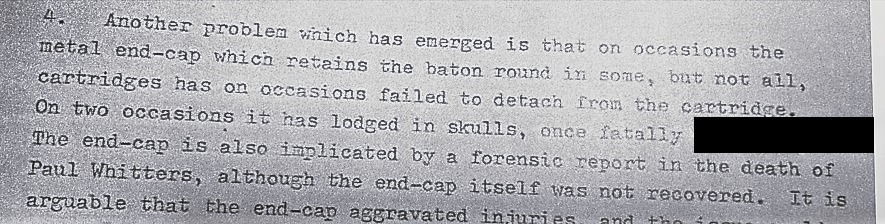

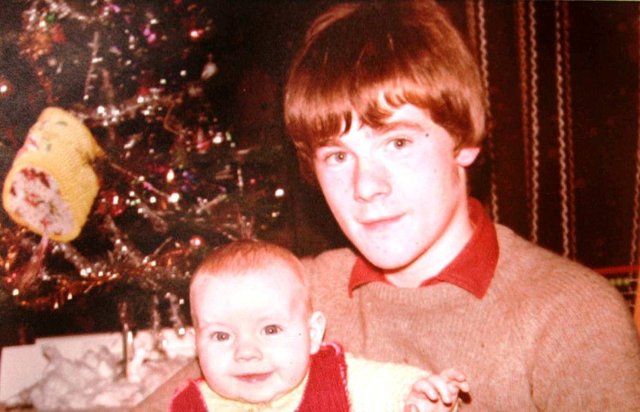

By 1982, the authorities were aware of a forensic report implicating a metal end-cap in the death of a 15-year-old Derry schoolboy, Paul Whitters, killed by a plastic bullet the previous year.

Paul was shot during street disturbances associated with the H-Block hunger strikes, causing him such catastrophic brain injuries that, ten days later, his parents agreed to his life support machine being switched off in a Belfast hospital.

Cover up

Thirty years later, his family discovered that in 2011 the British government had unilaterally decided to partially close the official file on the circumstances of his death until 2059, later extended to 2084 (half of it was open but 93 pages remained closed).

This was, allegedly, on grounds of data protection although the victim’s family had not asked for the names of those responsible to be released.

In any case, the name of the RUC man who had fired the bullet, and the Inspector who had issued the order, had been known since the inquest.

The family waged a four-year campaign for access to the full file, finally succeeding in October 2022 when the last two pages were released to them and their solicitor – Padraig Ó Muirigh – 41 years after Paul’s death.

Faulty ammo

In the file was a medical report stating that, during tests carried out on Paul Whitters’ body, the writer “formed the opinion that it [his injury] was likely to have been affected by a baton round carrying with it in flight, the metal cartridge seal”.

This revelation came, however, soon after London published its so-called “Legacy Bill”, which seeks to close down any legal paths for people bereaved in the conflict seeking justice through the courts.

This could mean the Whitters family is precluded from applying for a new inquest and from taking civil action seeking further disclosure.

The dead boy’s mother, Helen, told Declassified UK: “We are not giving up hope of a new inquest based on the new evidence. Clearly the MoD did all it could to prevent the public finding out while the police so-called ‘investigation’ was based on a false premise”.

The victim’s sister, Emma, who was born two years after Paul was killed, says it has been hard to watch her mother’s suffering over the years.

“The British government says it wants truth and reconciliation, but how is that possible when an inquest verdict stands, based on untruths and part-truths?”

Paul Whitters is not the only person where the metal caps are implicated in a fatal outcome. The same declassified document in which he is referenced names a 33-year-old man killed in July 1981.

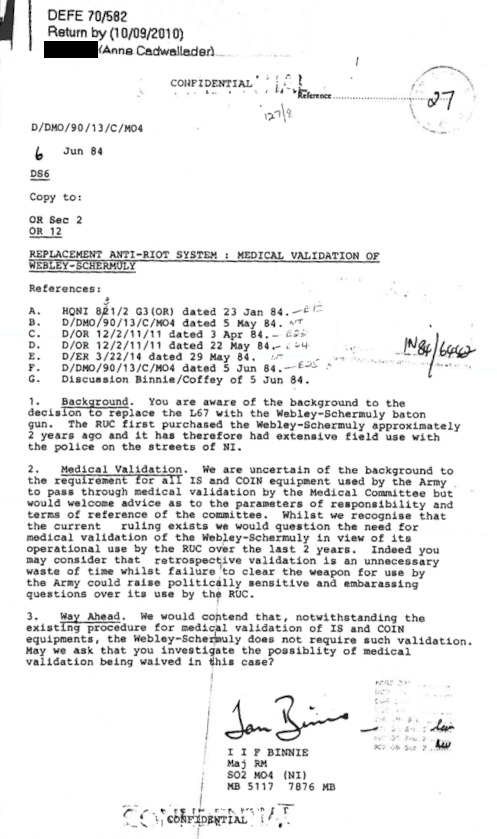

Untested guns

Plastic bullets continue to be used in Northern Ireland, most recently last year in Belfast when loyalists rioted against the implementation of the EU’s Northern Ireland Protocol.

This was despite an admission in a declassified document that the weapon was never fully medically validated.

The 1984 document, uncovered by The Pat Finucane Centre in the UK National Archives, states that, when the older-style “L67” plastic bullet gun was replaced with the newer “Webley-Schermuly” device, the move was not medically approved.

The document, which we found in 2010, states that the newer weapon had already been in “extensive field use with the police on the streets of NI” for the previous two years (i.e. since 1982).

Further, the document suggests retrospective medical validation might be “an unnecessary waste of time” as a “failure to clear the weapon for use by the Army could raise politically sensitive and embarrassing questions over its use by the RUC”.

Avoidable deaths

It would appear that the security and lives of people in Northern Ireland was trumped on this occasion by concern over “politically sensitive and embarrassing questions”.

These revelations, while they were broadcasted in a BBC Northern Ireland documentary this week, remain virtually unreported in Great Britain.

The first child killed by a plastic or rubber bullet in Northern Ireland was 11-year-old Francis Rowntree, shot dead on 20 April 1972.

An inquest ruled in November 2017 that his killing was unjustified and the soldier responsible had used “excessive force” causing skull fractures and lacerations of the brain.

More recently, a coroner presiding over a new inquest into the death by plastic bullet of yet another child, Stephen Geddis (aged 10), ruled that the soldier responsible had lied giving evidence.

A declassified document in this case revealed a handwritten note – added to a typed “Director of Operations” brief from 1975 – reading “Comfortable! In his coffin!”.

Alan Hepper, a senior principal engineer since 1988 at the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, was an MoD witness at Stephen’s inquest.

Hepper accepted in his evidence that no fewer than three government agencies had ruled by early/mid 1974 that plastic bullets should not be bounced off the ground, yet this continued to be the guidance given to soldiers.

The army’s prolonged use of faulty ammunition is not confined to Northern Ireland. Declassified uncovered how British troops in Kenya fired mortars fitted with faulty fuzes.

The fuzes would fall off on impact, rather than detonate. In 2015, a Kenyan boy picked up one of these mysterious metal objects, which exploded in his hands. The child lost both arms and an eye. The MoD knew the type of explosive used in the fuze was faulty six years before the incident.