In his first interview with the international media since being appointed to the new administration of President Alberto Fernández, Daniel Filmus told Declassified it is “impossible” that his government would try to militarily retake the Falklands. Argentina will continue to promote dialogue to resolve the status of the disputed islands, which the UK regards as an overseas territory, he said.

Filmus, the new government secretary for the Falklands, dismissed the UK government’s stated concern about future Argentine military action as an “excuse” for Britain’s own military and intelligence build-up against the South American country.

The Argentinian government has long been a target for British intelligence agencies. Filmus told Declassified he believes there is “an intelligence campaign against Argentina and Latin America to change attitudes”, in order to build support for continued British rule over the Falklands.

He also told Declassified that the Fernández government, which took office last December, would “re-examine” a UK-Argentine agreement signed in 2016 which increased “defence” cooperation between the two countries. Filmus added that his government will accelerate the “defence of the natural resources” around the Falklands, called “Las Malvinas” in South America.

Demanding demilitarisation

The new government will “demand very strongly” the demilitarisation of the South Atlantic, Filmus said. On the subject of the British military base on the Falklands – where Britain has at least 500 troops – he said bluntly, “It has to be dismantled.”

The UK regularly conducts military exercises, which include the firing of air defence missiles, on and around the islands.

Filmus added, “There is no justification for a military base that does military exercises every year in front of a country like Argentina that has said that we have no hypothesis for conflict with UK or any country in the world.”

Information gleaned from the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MOD) by Declassified shows that in the financial year 2018-2019 the UK government spent £22.3-million running its military base on the Falklands, more than it spent on its bases in Oman, Bahrain, Qatar, UAE, Singapore, Brunei, and Belize combined. In the same period, the UK spent £5.5-million running its military base on the Ascension Islands, also in the South Atlantic.

“We are going to go to all the multilateral organisations, not just in Latin America, but in America, and put down that the zone of the South Atlantic has to be a zone of peace without military bases,” Filmus said.

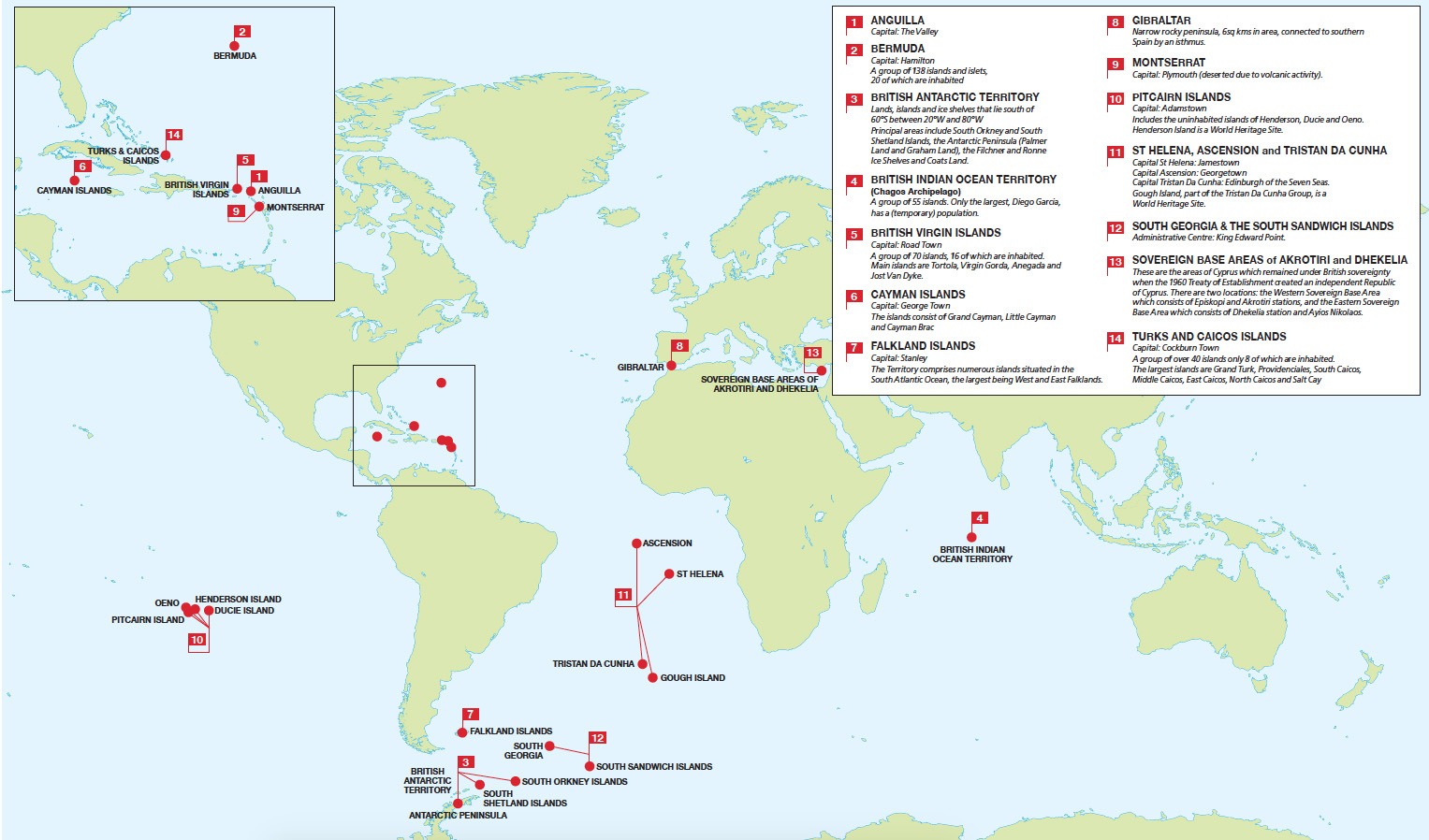

The UK controls a number of islands in the South Atlantic claimed by Argentina, including the Falklands, which it conquered in 1833, South Georgia, which it has managed since 1775, and the South Sandwich Islands, over which the UK claimed sovereignty in 1905. The Falklands has a population of 2,800 while the other two islands have no permanent inhabitants, although the British Antarctic Survey operates bases on South Georgia.

In his inaugural speech in December, President Fernandez said: “We reaffirm our strongest commitment to… and we shall work tirelessly to boost the legitimate and imprescriptible sovereignty claim over the Malvinas, South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands”. He added, “We shall do it knowing that the people of Latin America and the world are supporting us.”

Argentina’s position centres around UN resolution 2065 which was passed by the General Assembly in 1965. Referring to “the cherished aim of bringing to an end colonialism everywhere in all its forms, one of which covers the case of the Falklands Islands”, it instructs Argentina and the UK “to proceed without delay with the negotiations”.

Since the invasion of the Falklands by the Argentine military junta in 1982, the UK has refused to enter into a dialogue with Argentina over the status of the islands.

“My opinion is that sooner or later the UK is going to reestablish negotiations with Argentina,” Filmus told Declassified. “There is no place now for a colonial system in the 21st century. We are going to work always through peaceful means and diplomacy to make this a reality.”

A UK government spokesperson, meanwhile, told Declassified: “Our position on the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands is in no doubt, with the Islanders making clear they wish to remain a part of the United Kingdom.”

A British coup

The UK has since 1982 prohibited arms exports to Argentina judged to “enhance” its “military capability”. In 2012, the UK imposed “additional restrictions” on Argentina, accusing its left-wing government of “escalating actions aimed at harming the economic interests of the Falkland Islanders” – referring to Argentina’s attempts to prevent British oil exploration around the islands.

These new restrictions meant the UK government would not to grant an export licence “for any military or dual-use goods and technology being supplied to military end-users in Argentina, except in exceptional circumstances”.

After the right-wing administration of Mauricio Macri swept to power in Buenos Aires in 2015, the British government said its relationship with Argentina was “improving”. The then-foreign secretary Boris Johnson visited Buenos Aires in May 2018, the first visit by someone in this position since 1993.

Filmus says that relations improved primarily because “the intensity of the claims from Argentina decreased”, and that the Macri government “stopped defending the natural resources” of the area around the Falklands. He has vowed to reverse both of these trends.

In the middle of this thaw in relations, in September 2016, Sir Alan Duncan, then minister for Europe and the Americas, concluded a two-day visit to Argentina and signed a “joint communiqué” which had been negotiated with deputy foreign minister Carlos Foradori.

The final point of what became known as the Foradori-Duncan agreement concerned the contested island territories and committed the two sides to “set up a dialogue to improve cooperation on South Atlantic issues”.

But, in a coup for the British, the agreement stipulated that both countries would now “take the appropriate measures to remove all obstacles limiting the economic growth and sustainable development of the Falkland Islands, including in trade, fishing, shipping and hydrocarbons”.

These obstacles had included firm Argentinian opposition to the UK prospecting for resources in the South Atlantic. In 2010, UK company Rockhopper Petroleum made the first significant discovery of oil deposits – estimated to be 242m barrels – off the Falkland Islands. At the time, this “raised hopes among other explorers in the South Atlantic region”. More discoveries came in 2015 and 2016.

Alicia Castro, Argentina’s ambassador to the UK from 2010 to 2015 under the left-wing Cristina Kirchner administration, told Declassified, “Under President Macri, relations with the UK didn’t get better for Argentina, they only got better for the UK. They actually got worse for Argentina because we were handing over the hydrocarbons around the islands, which is forbidden by law.”

Military training

The 2016 communiqué also mentioned that the countries “agreed to strengthen relations between the two armed forces”. The UK soon held “strategic defence dialogue” talks with Argentina for the first time since 2006, which focused on “identifying opportunities for sharing information and experience in various fields”.

In 2018, as the relationship with the Macri administration continued to strengthen, London lifted the additional restrictions placed on Argentina in 2012. Duncan said that while the UK would still not export anything judged to increase Argentine military capability, “where like-for-like equipment is no longer available, we may grant licences where we judge they are not detrimental to the UK’s defence and security interests”.

Declassified can also reveal that at some point since 2015 Argentina sent personnel to the UK for military training, according to information we recently gleaned from the Ministry of Defence (MOD).

It is likely that this was part of the new military cooperation and may also have been linked to Argentina loosening its opposition to UK prospecting for oil around the Falklands. It would also seem to contradict the UK policy, outlined for arms exports, not to “enhance Argentine military capability”.

Declassified requested information from the MOD about this military training but it declined to answer, stating that “personnel security” would be violated. However, the day after the MOD refusal, the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, which is part of the MOD, tweeted a picture of five cadets – with unobscured faces – from Bahrain, Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Maldives who were attending military training at the academy.

The new period of military cooperation may not last. Filmus confirmed to Declassified that the new Argentinian administration is “studying” the 2016 Duncan-Fiordoro agreement to decide on its merits going forward. A UK government spokesperson, meanwhile, told Declassified:

“We are regularly in contact with the new administration in Argentina and look forward to building on the 2016 joint communique.”

Intelligence operations

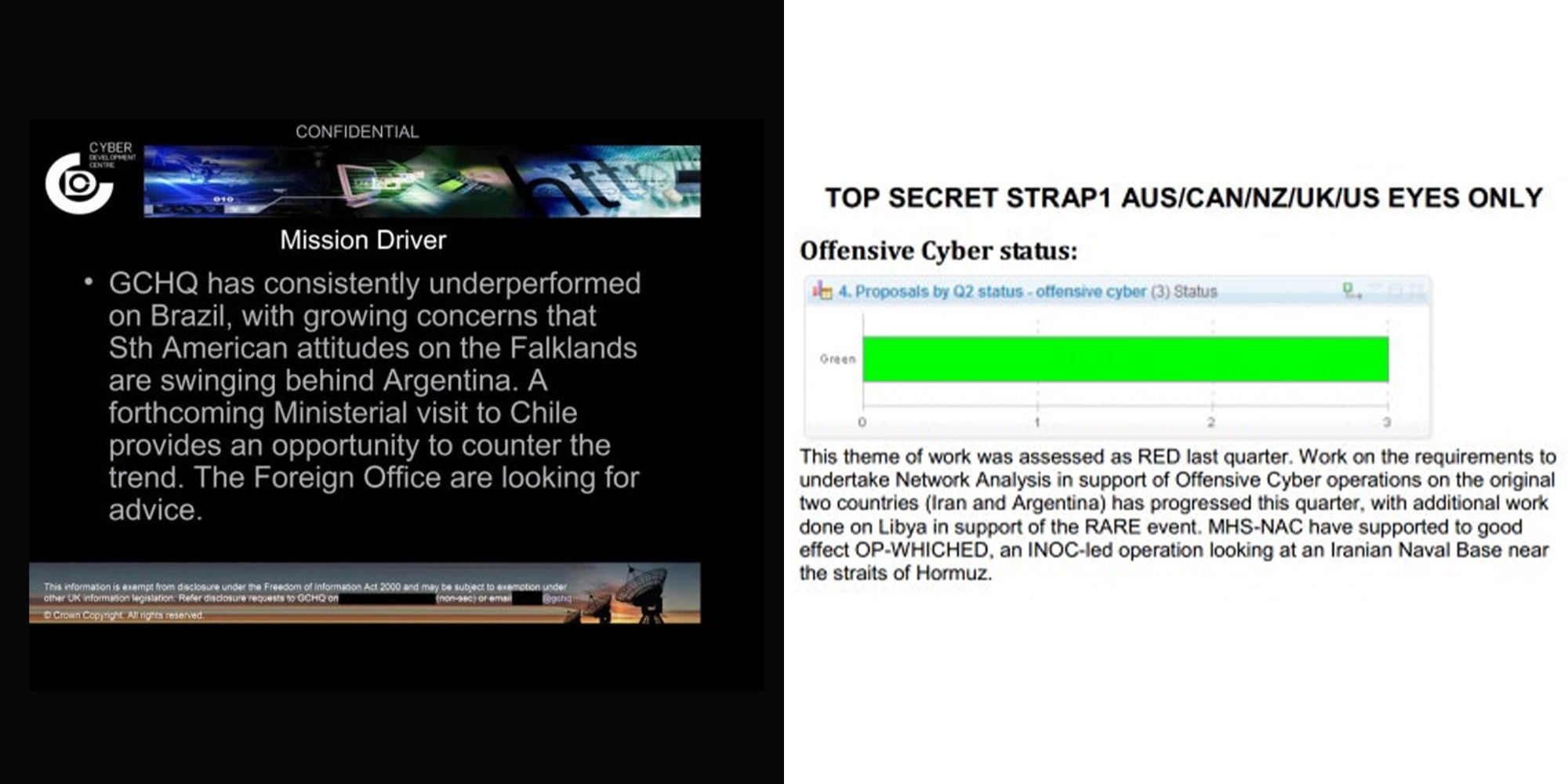

In 2015, revelations from NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden exposed offensive cyber programmes run by British surveillance agency GCHQ against Argentina ostensibly to prevent the country’s military takeover of the Falklands.

The Joint Threat Research and Intelligence Group, a secretive GCHQ unit, was revealed to have managed, and possibly still manages, a “long-running, large scale, pioneering effects operation” against Argentina.

Given the name Operation Quito, the aim was “to support” the UK Foreign Office’s “goals relating to Argentina and the Falkland Islands”. Surveillance of Argentine “military and leadership” communications across a number of platforms was – and likely still is – a “high priority” task.

Documents from Snowden further suggested that GCHQ was running a programme aimed at “preventing Argentina from taking over the Falkland Islands by conducting online HUMINT [human intelligence].”

As the Intercept reported: “Online HUMINT is the collection of information on human targets through passive tracking or overt interaction with a target through an alias. These operations may sometimes be in support of, or in conjunction with, covert MI6 agents on the ground.”

Filmus believes that the UK’s stated concern about possible Argentine military operations against the Falklands is not genuine.

“I don’t think they are concerned about military action in any way,” he told Declassified. “I think it’s part of an intelligence campaign against Argentina. They know the position of Argentina, they know the reality of Argentina, nobody can imagine that Argentina is going to consider military action.”

He continued: “What Snowden showed us, rather, is that there is an intelligence campaign against Argentina and Latin America to change attitudes.”

GCHQ admitted in the documents leaked by Snowden that it had failed in its goal to create significant support in the region for continued British rule over the Falklands.

Filmus added he has seen no evidence of British intelligence operations against him personally, although he would fit the profile of individuals previously targeted by GCHQ for “high priority” surveillance.

A request for comment put to the British embassy in Buenos Aires was not returned.