At least ten people with alleged or known links to British intelligence agencies or covert warfare now hold key roles overseeing government.

The murky past of some of these figures means they are strictly off limits to full public scrutiny. Some might think this makes them an odd choice to enforce accountability.

Here’s a short survey of this increasingly fashionable career path.

1. Sue Gray: Partygate inquisitor-in-chief.

Now one of Britain’s most senior civil servants, Gray took an unusual career break in the 1980s to run a rural pub in Northern Ireland with her husband, a musician. The couple chose a remote location near his roots in County Down. It was then the height of the Troubles and this pub was not far from IRA strongholds along the border.

Dr Kevin Hearty, a criminologist at Queen’s University Belfast, told Declassified: “It’s certainly become clear in subsequent years that intelligence agencies were operating people like Peter Keely aka Kevin Fulton [an IRA informer] in that immediate area at that particular stage.

“The fact we know next to nothing about Sue Gray’s time there, or her past more generally, certainly adds a further layer of intrigue to the whole thing.”

Even the BBC seems unable to rule out whether Gray was a spy. Radio 4 said: “More than one person we’ve spoken to has suggested that Sue Gray might have been involved with the secret services. This might explain the lack of information about her personal life and family background.”

When asked by BBC Northern Ireland if she was a spy, Gray didn’t directly deny it, instead saying: “I think if I was a spy I’d be a pretty poor spy.”

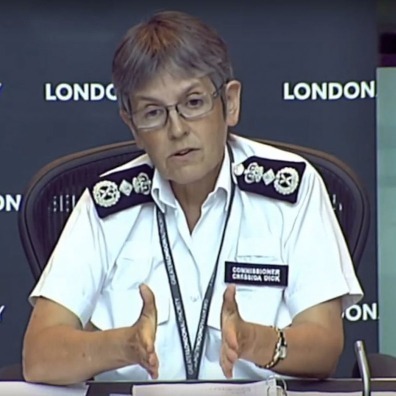

2. Dame Cressida Dick: Head of the Met

The Met police commissioner is another partygate referee who has a mysterious gap on her CV. Despite overseeing the controversial fatal shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes in 2005, she was seconded to the Foreign Office in 2015 for an anonymous security role. Many assume the posting was cover for MI6. Dick’s belated police probe of Downing Street’s drinking culture has led some to suspect a stitch-up.

3. Simon Case: GCHQ’s man

One person who definitely worked for British intelligence is Simon Case. He was Director of Strategy at GCHQ. Now Cabinet Secretary and effectively the UK’s top civil servant, he was originally picked to lead the partygate probe until it emerged a knees-up was held in his own office during lockdown.

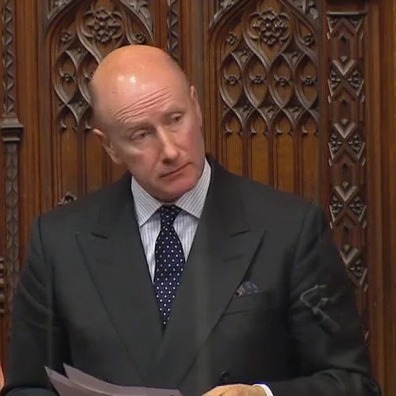

4. Lord Jonathan Evans: MI5’s man

An ex-head of MI5 who now chairs the government’s Committee on Standards in Public Life. His appointment raised eyebrows at the time given he had six other paid jobs. We are allowed to know almost nothing about Evans’ MI5 career. Perhaps he could shed light on Sue Gray’s spell as a pub landlady.

5. Baroness Eliza Manningham-Buller: MI5’s woman

6. Lord Christopher Geidt: The Sultan’s man

A former army intelligence officer, his job is to make sure ministers – including Boris Johnson – have properly declared their financial interests.

Now famous for probing Downing Street wallpaper, he’s less keen to answer questions about who paid for his private jet trips to Oman. There, he was a secret member of the Sultan’s Privy Council, and together with the head of MI6 advised that Gulf autocrat how to run his oppressive regime.

7. Lieutenant Colonel Tobias Ellwood MP: The psyops man

Despite being a reservist in the army’s 77th Brigade – a secretive information warfare unit – he chairs parliament’s defence committee, a powerful body which is supposed to scrutinise the UK military. We still know next to nothing about the 77 Brigade’s role in domestic information operations on coronavirus.

8. Tom Tugendhat MP: The committee’s man

He chairs the parliamentary committee tasked with overseeing the Foreign Office and now wants to replace Boris Johnson as prime minister. The son of a High Court judge, he studied Islam at Cambridge and learnt Arabic in Yemen before joining the army’s intelligence corps. He served in Iraq and later the Foreign Office sent him to Afghanistan to advise its national security council.

9. Stephen Hawker: MI5’s censor

A former deputy head of MI5. He sits on the government’s censorship watchdog, the Advisory Council on National Records and Archives (ACNRA). Their job is to make sure Whitehall papers are not unnecessarily withheld from the National Archives once they turn 20 or 30 years old.

MI5 is not required to release any of its historic papers to the National Archives. Even if it was, it probably need not worry. The ACNRA rubber stamps around 99% of government censorship requests.

The National Archives refuses to explicitly say on their website that Hawker used to be very high up at MI5. Instead he’s listed as “a former senior security and intelligence official.”

10. Martin Howard: GCHQ’s censor

He sits alongside Hawker at the censorship watchdog and has a similar pedigree. Howard was deputy chief of Defence Intelligence in the months before and after the invasion of Iraq. His last job in government was Director for Cyber Policy and International Relations at GCHQ.

The National Archives prefer to call him a “retired senior security official”. Like MI5, GCHQ doesn’t have to hand over any of its old files to the National Archives or answer freedom of information requests.

Whatever such people now overseeing government got up to when they worked in intelligence, we will probably never know.

So why should we trust them to referee transparency and standards in public life?