GCHQ is promoting a programme in dozens of primary and secondary schools where children are being taught how to launch a “cyber attack” against “a large school or university”, how to hack passwords and “vulnerable machines”, and how to spy on other children’s wifi traffic.

The programme, known as the Cyber Schools Hub or CyberFirst, is operated in partnership with Cyber Security Associates (CSA) – a company set up by former members of the Ministry of Defence (MOD)’s Joint Cyber Offensive Unit, which is housed at GCHQ headquarters in Cheltenham, southwest England.

Documents seen by Declassified suggest that CSA has worked closely with GCHQ to design the schools programme from the beginning, and that GCHQ is using taxpayers’ money to pay the company to develop “cyber security” products.

CSA has also hosted dozens of children at its offices as part of a work experience programme. It is not known if parents are told that the company is run by former government cyber warfare specialists.

The sensitive nature of the skills children are being taught is illustrated by a disclaimer in CSA material which states: “The misuse of the information in this document can result in criminal charges brought against the persons in question.”

CSA was established by David Woodfine, a former commander of the Joint Cyber Offensive Unit, the month following his departure from the MOD. His co-director, James Griffiths, was an “operator providing cyber offensive capability” in the same unit.

The unit’s existence appears to have only ever been recognised in online biographies of Woodfine and Griffiths and it is not known what operations it has been involved in.

Declassified has also seen evidence that CSA has been provided with equipment by GCHQ to incentivise it to go into the schools, to “help develop activities based on the roles within a Security Operations Centre”, which is another cyber unit in the MOD that Woodfine commanded for a number of years.

CSA was incorporated as a company in April 2016, the month before GCHQ’s schools programme was launched. Woodfine and Griffiths have established eight variants of CSA, with slightly different names, since 2013.

GCHQ runs the Cyber Schools Hub (CSH) programme through one of its arms, the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), which opened in 2016.

The NCSC and CSA did not respond to questions about whether CSA was set up with GCHQ’s blessing to help run its schools programme.

“Training school students into the murky world of cyber warfare under the guise of improving their aspirations is immoral, dangerous and deeply worrying,” said Emma Sangster, coordinator of ForcesWatch, an organisation set up to track the militarisation of British society.

“The creep of the security state into schools is not receiving the public scrutiny it deserves. Not only is the understandable interest of children and teenagers in this area being exploited for the benefit of under-the-radar interests, but facilitating activities such as hacking puts young people at risk by encouraging potentially illegal activity.”

Sangster added: “We hope that parents and school governors will look carefully at the duty of care implications and challenge the involvement of their schools with the state’s security forces.”

Declassified has revealed that the CSH programme is promoting arms corporations involved in war crimes overseas to British school children. It has also been revealed that GCHQ officers themselves are operating in at least one school, while parents of pupils at schools across the programme do not appear to have been informed about the extent of the spy agency’s role in it.

GCHQ divulges little information about the schools programme and did not respond to queries for this article, but Declassified has seen a newsletter produced for a short period from December 2018 to July 2019, which gives some details.

Online covert action

The UK government has a National Offensive Cyber Programme, run jointly by the MOD and GCHQ, which has a budget of £250-million and 2,000 staff.

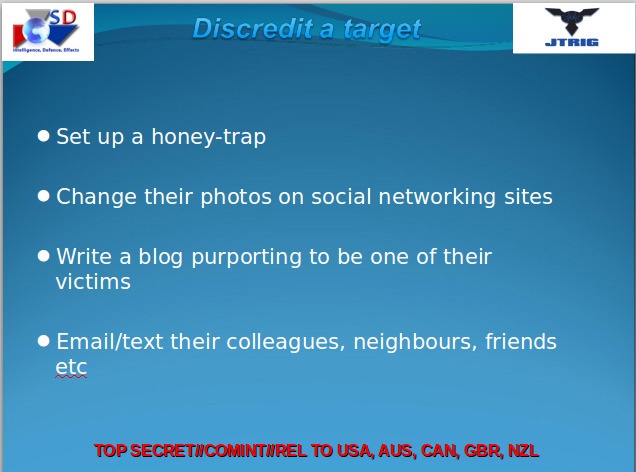

Disclosures from US whistleblower Edward Snowden in 2013 revealed that GCHQ has a secret cyber warfare unit, named the Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group (JTRIG), which takes five percent of the organisation’s budget. Its stated purpose is to “destroy, deny, degrade, disrupt” enemies by “discrediting” them, and its operations include “honey traps”, “false flags” (posing as an enemy) or “writing a blog purporting to be one of their victims”.

According to Richard J Aldrich, a professor at Warwick University in central England and author of the authoritative history of GCHQ, “One of the enemies on JTRIG’s list is investigative journalists who pose a ‘potential threat to security’”.

JTRIG also undertook a “pioneering effects operation”– or cyber warfare programme – against Argentina, a friendly country with whom the UK is not engaged in hostilities. Documents released from the Snowden archive do not cover the Joint Cyber Offensive Unit (JCOU), whose activities are likely to be just as sensitive.

Before running JCOU, Woodfine was commanding officer of the Security Operations Centre at the MOD base at Corsham in Wiltshire, which is the centre of the UK’s cyber warfare activities.

His partner, James Griffiths, who worked at GCHQ on cyber warfare for five years, was previously in the British Army and “specialised in information systems”, being deployed at home and overseas, and “often working with special forces in hostile environments”. It is possible Griffiths was deployed in one of the seven covert wars being fought by Britain’s special forces in places like Syria and Libya.

Last year, the British parliament’s oversight body, the Intelligence and Security Committee, found evidence that GCHQ had played a role in supporting the CIA’s post-9/11 kidnap and torture programme.

The committee unearthed examples of GCHQ’s intelligence being used to locate and detain terrorism suspects who were subsequently rendered and tortured, as well as providing intelligence to assist the interrogation of terrorism suspects held at CIA “black sites”.

CSA and GCHQ

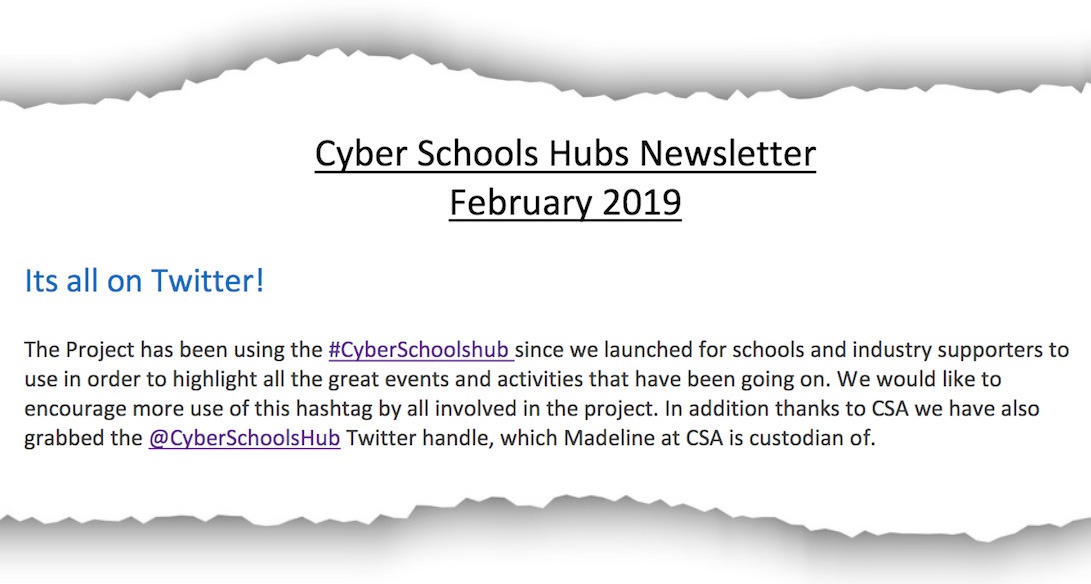

According to documents seen by Declassified, CSA has worked closely with GCHQ to design the Cyber Schools Hub programme – which was set up in 2017 – from the beginning. A staffer from CSA, identified only as Madeline, created and ran the now-defunct @CyberSchoolsHub twitter handle which GCHQ used to promote the project.

Months later, the same Madeline “spent a day every week with the NCSC team”. She was entrusted with several tasks by GCHQ “including overhauling the CSH informal website and correlating and coordinating industry support requirements from schools”. Madeline was also given an @cyberhub.uk email address.

It is assumed the Madeline referred to in the documents is Madeline Howard who was previously Business Development Manager at CSA, during which time she gave talks in schools involved in GCHQ’s programme. The then 21-year-old Howard began working for CSA soon after it was incorporated, helping to publicly promote the company.

She is now director of CyNam – “a Cheltenham-centric platform that connects the best cyber security minds and local [businesses] and start-ups” – which is closely linked to CSA.

Howard is emblazoned on the frontpage of a new magazine, produced by Cheltenham Borough Council, promoting the council’s Golden Valley development, which will include a £400-million “cyber campus” on a 200-hectare site next door to GCHQ.

In her article, Howard writes extensively of GCHQ’s schools programme, saying that it “seeks to give young students the space and the opportunity to excel and explode into the market of cyber security and innovation”.

When a steering group made up of representatives from companies involved in the project was created to develop industry engagement further, Madeline was GCHQ’s point of contact “if you or your company would like to be involved in this group”. At the Cheltenham Science Festival, attended by school students, GCHQ sponsored the Cyber Zone area and included a CSA exhibit.

GCHQ, meanwhile, has facilitated the entry of both CSA’s co-founders, Woodfine and Griffiths, into schools in Gloucestershire to work with children.

The CSA website has three pages on its “About” section, one of which is dedicated to the Cyber Schools Hub. The company is one of only two “partners” in the programme and is an “approved school supplier” which allows it to provide cyber projects and vocational courses for schools “across the UK”. In 2019, the company had 11 staff.

David Woodfine told Declassified in March 2019 that CSA has contracts with GCHQ and that it also offers “a range of cyber managed services to the commercial market”. It is not known if parents of children involved in the CSH project have been made aware of CSA’s connections to GCHQ.

Cyber warfare and hacking for kids

In early 2019, CSA launched its flagship educational product, named the Cyberdea Immersive Zone. Built on the bottom floor of the CSA offices in Quedgeley, a small town south-west of Gloucester, Cyberdea is a specialised cyber training facility primarily for use by school students. Able to host up to 24 children at a time, the facility offers a range of courses for all abilities.

One seven-hour course for basic to intermediate level – which runs for school hours of 9am to 4pm – is titled “cyber offensive session”. The promotional blurb says that the class will “fully immerse the students into the mindset of a cyber attacker where they will be taken through the reconnaissance, analysis, penetration and exploitation phases of a cyber attack”.

It adds, “Using our simulated and virtualised environment, a number of realistic networks and scenarios will be available to attack. These range from a small business network to a large school or university network.”

According to documents seen by Declassified, from February to March 2019, seven Gloucestershire schools booked to bring their students to Cyberdea for training. It is not known if these included primary schools.

The NCSC says that having the Cyberdea facility close to the schools in the programme helped, because after trips to Bletchley Park and the Bank of England, “the project teachers informed us that these… required a lot of paperwork overhead”. Lighter paperwork was apparently needed to send children to Cyberdea.

It is unclear if Cyberdea was created by CSA on a contract from GCHQ. The Cyber Schools Hub logo appears prominently on the Cyberdea website.

The second major project CSA has devised for GCHQ’s schools programme is called Cyber Pi, a series of boxes containing projects on small single-board computers that introduce children to programming and hacking.

As one CSA staffer puts it, the project gives the children “hands on opportunities to try out these things that they’ve heard about on TV, and seen in movies.” The boxes include a “wifi jammer project”, and a “rogue access point project,” where children can spy on other children’s wifi traffic.

Brute force

Despite government funding for the schools programme being classified, Declassified has seen evidence that GCHQ is using taxpayers money to pay CSA to develop hacking and other products for use by children in schools. CSA appears to be the only company producing technology specifically for the CSH project.

One newsletter notes that the GCHQ team “asked if CSA could develop 12 new projects based around the Internet of Things as part of purchasing an additional classroom drop crate of 15 Cyber Pi Kits”. It adds, “CSA did a fine job and have hosted the new projects on the Cyber Pi website”.

Drop-crates including the Cyber Pi boxes were initially distributed by GCHQ using a courier service. But the surveillance agency then decided it would be better to have “distribution centres”, with its own booking system, and the CSA office in Quedgeley was designated one such centre.

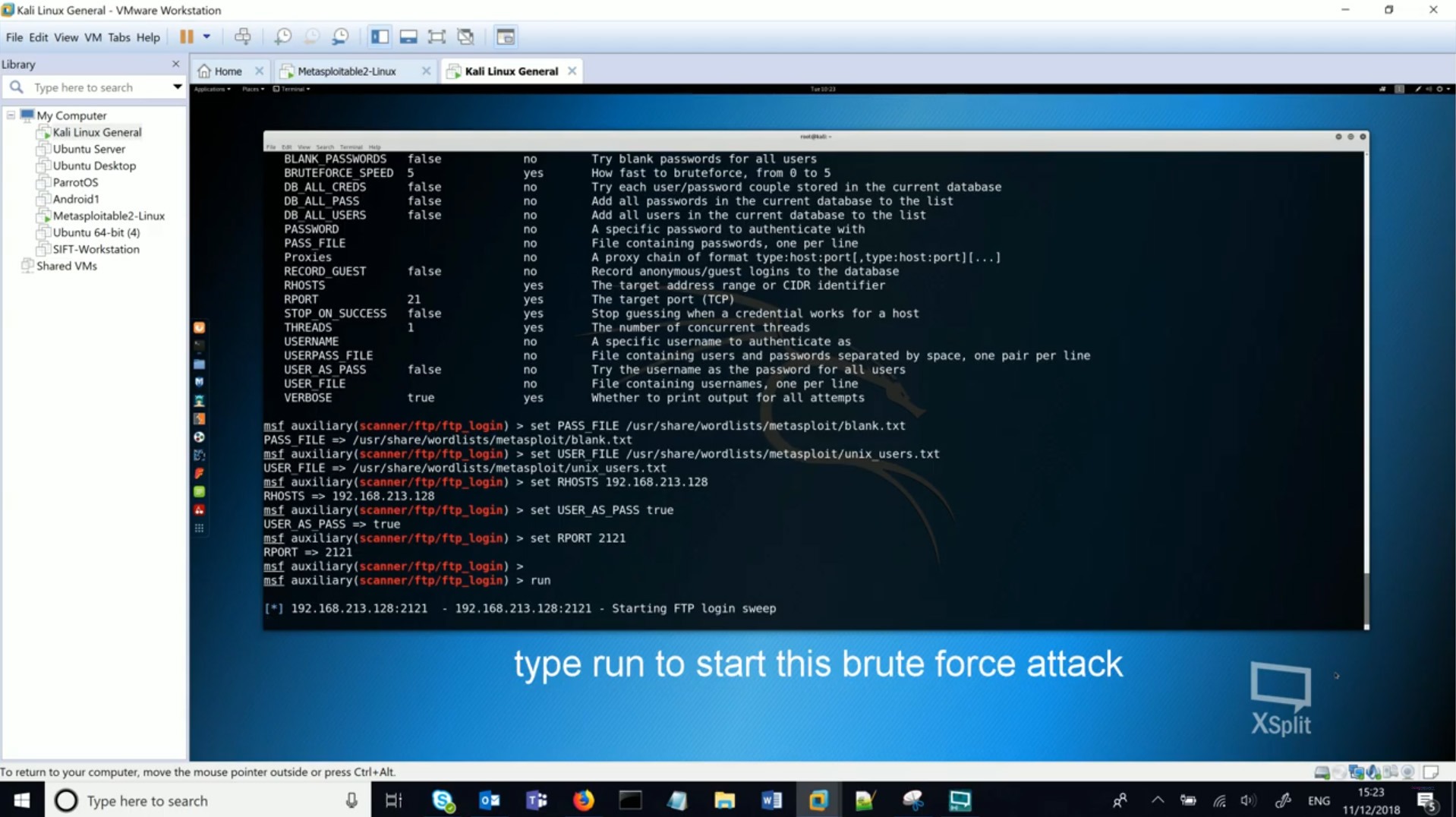

As part of the Cyber Pi project, “Jamie at CSA” – assumed to be James Griffiths – set up a “hacking server” configured to have 12 vulnerable “virtual machines” running. This allows students to connect to the network and “test their skills at exploiting and hacking the vulnerable machines”. This was said to be based on experience that CSA had gained from “developing products for commercial customers”.

The hacking video classes – overlaid with trance music – include lines like “once the exploit has completed properly… we can… explore the target machine” and “make sure the victim machine is active”. One lesson titled “Brute Force” instructs the children to “type run to start this brute force attack”. There are 24 projects available.

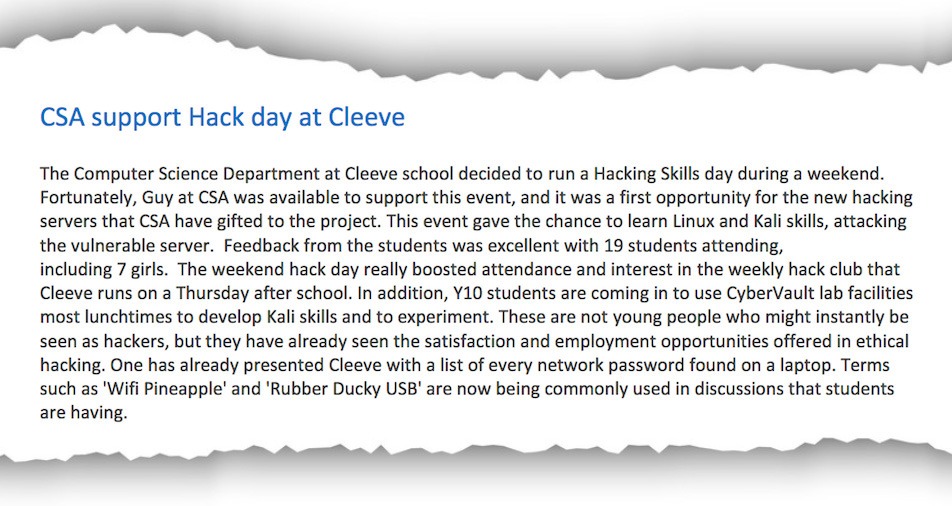

CSA also supported a weekend “Hack Day” for 19 students at one school, which saw them “attacking the vulnerable server” provided by the company. “These are young people who might not be instantly seen as hackers, but they have already seen the satisfaction and employment opportunities offered in ethical hacking,” the newsletter notes.

It adds that one student presented Cleeve, a school near Cheltenham which is the lead “hub” in the schools programme, “with a list of every network password found on a laptop”.

The nature of the skills being imparted is clearly sensitive. CSA includes a disclaimer in its materials stating: “The misuse of the information in this document can result in criminal charges brought against the persons in question.”

“Improving student aspirations”

At Beaufort school, a 20-minute walk from CSA headquarters in Quedgeley, David Woodfine “took time out of his calendar to chat and meet with students, holding a question and answer session”, a newsletter notes.

It adds that “as a way of trying to improve some of the student’s [sic] aspirations”, the former head of MOD’s offensive cyber operations shared “his own personal story and understanding of opportunities that are presenting themselves for students looking to move into the cyber security career field when they leave education”.

Declassified has seen evidence that CSA has also been provided with equipment by GCHQ to “help develop activities [in schools] based on the roles within a Security Operations Centre”, which is another cyber unit that Woodfine previously commanded.

CSA appears to have deeply penetrated British schools, entering numerous of them on a regular basis to roll out its Cyber Pi project. It also appears that a staffer from CSA was appointed to the board of “Women in Cyber” at Wyedean school, just north of Bristol.

CSA is revealed in the newsletters to be “working closely” with Wyedean school “to help develop appropriate learning material for both students and teachers”. Students from this school were then used by CSA to test the company’s new technology. “As a thank you and to also help CSA test their new… concept, CSA hosted 24 female students at their facility in Quedgeley for the day.” The experience “was hyped as part reward for some excellent school work”.

In 2019, female students were selected from four CSH schools to attend a Wyedean-organised “cyber day” at the University of South Wales. The teachers and students were joined by staff from CSA.

When students at Wyedean came up with the idea of creating a CyberTV channel to document their involvement in the CSH project, the first episode involved CSA staff, in addition to Wyedean students, and was shown within GCHQ itself.

Another Wyedean project involved an event based on the BBC One series, The Apprentice. The school sourced its own panel of experts, including staff from CSA and BAE Systems, the UK’s largest arms exporter, while the NCSC’s director of operations, Paul Chichester, took the “starring role” as Alan Sugar.

The CSH programme also runs “Cyber Nights” where primary and secondary school teachers are educated by CSA “on hacking techniques”.

Ribston Hall school in Gloucester held a cyber day for Year 8 students, in which CSA participated. One session on the day was titled “Popstars and Passwords” and focused on how to hack passwords. “Student feedback showed that they found the whole day very enjoyable and informative, with the industry perspectives and activities being the highlight of the day,” noted the newsletter.

In March 2019, the CSH project held an “industry support recognition evening” in Gloucester at which the NCSC team gave out awards to specific companies for their involvement. Winner of the small enterprise award was CSA, which was also one of only two organisations awarded the most senior “partner” status in the CSH project.

The other “partner” is the South West cyber crime police unit. Arms companies Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman achieved only “associate” status.

Work experience

CSA has also hosted dozens of children at its offices as part of its work experience programme. GCHQ noted in December 2018 that CSA was “expanding the numbers of students that they can accommodate”.

Seven months later, in July 2019, CSA was praised by GCHQ for “once again doing a massive job of supporting the project schools with work experience opportunities”, a system of placements which “continues to grow”.

The newsletter noted that in 2018 it was just two students a week but in 2019 “they have provided work experience for three students at a time given the interest”. In the two months from June to July 2019, 17 students were placed at CSA. It is unknown if this rate has continued.

At least five of the schools placing their students at CSA were not officially part of the CSH programme, raising further concerns about duty of care and consent. These non-affiliated schools included Bredon School in Gloucestershire, which is a specialist school for children as young as seven with learning difficulties.

It is possible that another of the schools, identified only as “Malmesbury”, is a primary school since this town in Wiltshire has both primary and secondary schools.

The software director at Deep3, another “cyber security” company, was said to be “hoping to be able to get his company into a similar position as CSA and be able to offer work experience opportunities to large numbers of students, as he realises the impact this has on their career choices”.

After answering questions on Declassified’s first investigation of its school programme, the NCSC did not respond to further questions about the role of CSA. David Woodfine, James Griffiths and Madeline Howard were approached for comment for this article, but none responded.

Parts 1 and 2 of this investigation can be read here and here.