Saif al-Islam Gaddafi paid an Australian special forces veteran to help organise the defence of Tripoli during Nato’s bombardment of Libya’s capital in 2011, a book reveals.

John Gartner, director of Osprey Asset Management (OAM), claims he arranged for up to 150 South African and Russian mercenaries to support the North African dictator.

However, anti-Gaddafi rebels backed by Nato aircover took power before the foreign fighters could be deployed.

Writing in his memoirs, The Fading Light, Gartner says the Gaddafi regime gave him approval “to contact my colleague in Moscow, a former senior KGB (later FSB) officer now establishing his own private military company”.

The Russian company, which Gartner does not name, was aspiring to guard Gazprom and Lukoil projects in Iraq.

Although Gaddafi’s regime fell before Gartner’s men could be deployed, other Russian mercenaries from the notorious Wagner group would fight in Libya’s subsequent civil war.

Wagner fought for Libyan General Khalifa Haftar, who the UN has accused of committing atrocities. Wagner, which was formed after the Arab Spring, is now believed to have deployed to Ukraine.

An Australian in Tripoli

John Gartner was first approached in 2002 by Muammar Gaddafi’s son, Saif al-Islam, who explored the possibility of OAM training bodyguards for the “close protection” of his family.

A senior official from Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade personally met Gartner in Perth and allegedly gave him clearance that “this training would not breach Australian legislation”.

Gartner drafted a training program and assembled a provisional team of “former SAS operators” to act as instructors, but ultimately the project did not go ahead.

Fast forward to 2011, the Gaddafi family was once more in need of security support, and they called on Gartner again.

He flew to Tunisia and travelled by car to Tripoli in August 2011, when the Libyan capital was “under almost daily aerial bombardment from Nato air forces”.

A representative of Saif al-Islam then briefed him over dinner by the swimming pool of the Radisson Blu hotel, “while intermittenly bombs detonated around Tripoli”.

Gaddafi’s son had initially wanted Gartner to provide him with bodyguards, “but by the time I had arrived in Tripoli, expectations had become more ambitious.”

“I was now tasked with advising Libyan combat capable formations in the field, operationally,” Gartner said. “In the view of the Libyans, I was the specialist, it was therefore up to me to determine their exact needs, the costs involved and time frame.”

The next day, Gartner lined up 50 South African “consultants” and provided Libyan authorities with their passport details to fast-track their visas.

He then left Libya by land, entering neighbouring Tunisia undercover as a mining specialist and stopping over at Djerba, an island resort near the border. There, Gartner gave an associate 10,000 US dollars in cash “to cover his immediate expenses” as his “man on the ground.”

Within a few days, rebels were threatening the highway from Tripoli to Tunisia, jeopardising Garter’s access route. Undeterred, he moved half of his South African team to Djerba, “ready to deploy into Libya the moment the call came”.

The Serbian suggestion

Saif al-Islam’s representative, who had been Gaddafi’s chief pilot, then asked to meet Gartner in the Lebanese capital Beirut, where he requested another 100 mercenaries, preferably from Serbia.

Over dinner at a five star seafood restaurant, Gartner advised strongly against hiring Serbians, warning they had a “reputation for brutality” and would be a “poor proposition in the battle to win the international publicity war”.

Instead, Gartner suggested a “Russian group in Moscow, comprised of former Special Forces soldiers who had fought in Afghanistan and Chechnya”.

He was given approval by the Gaddafi regime to pursue his Russian contact, but later that month Tripoli fell to rebel forces before the second half of his South African staff had even reached Tunisia.

“I was shocked by the sudden turn of events, as nothing had prepared me and my team members for such a sudden reversal of fortunes for the Libyan army,” Gartner commented.

“The bloody end to the Gaddafi regime did not immediately signal the conclusion of my contract, as I had been employed by Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, not his family, and I held out hope that he would continue to defy the rebellion and reassert his own authority.

“But with Saif’s paymaster now having gone missing, and no chance of further payments coming my way,” Gartner withdrew his men from Tunisia and told the remaining contingent in South Africa to stand down.

Saif al-Islam was captured by rebels but released in 2017. Despite being wanted by the International Criminal Court, he is running in Libya’s presidential election in June.

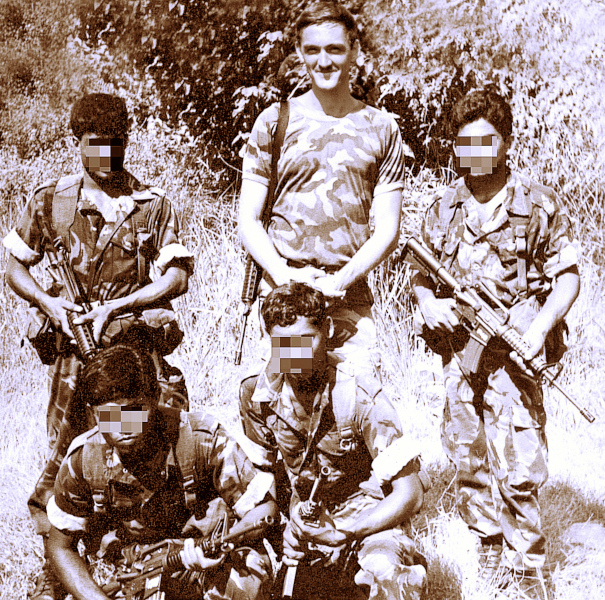

Profile: A gun for hire

John Gartner joined the Australian army in 1971 and became one of the youngest soldiers to enter its elite Special Air Service, aged 19.

Frustrated at missing Australian SAS deployments to Vietnam, he moved to Rhodesia in 1974 and fought in defence of Ian Smith’s white minority government.

Following their defeat by black nationalist forces, Gartner relocated to South Africa in 1980 where he joined the apartheid regime’s security apparatus.

He was assigned to Operation Barnacle, a secret mission to sabotage Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC) and its allies.

It saw him conduct covert operations in Zimbabwe, Botswana, Swaziland, Lesotho, Zambia, Namibia, Angola and Mozambique until 1986.

Thereafter, he joined Keenie Meenie Services (KMS), a British mercenary company embroiled in Sri Lanka’s brutal civil war with Tamil independence activists.

From 1986-88, Gartner trained Sri Lankan military units, who he felt were “very nationalistic, and supremely chauvinistic when it came to their views about the Tamils, which I used to reinforce my training message”.

His assignment saw him “in the front line and advising infantry formations in situ” at a base on the northern Jaffna peninsula – a Tamil stronghold – although he claims never to have accompanied patrols on operations.

The Metropolitan police in London are investigating allegations KMS was involved in war crimes in Sri Lanka.

In 1989, KMS (renamed as Saladin Security) gave Gartner a new role guarding Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani, Saudi Arabia’s former oil minister.

After six years shadowing Yamani, he left Saladin and found work advising Brunei’s notoriously corrupt royal family on security.

Then in the late 1990s, Gartner founded his own mercenary company, Osprey Asset Management (OAM).

It would go on to guard gold mines in Indonesia, escort convoys delivering new police vehicles to Abu Ghraib in Iraq, and advise iron ore projects in west and central Africa.

John Gartner did not respond to a request for comment.

A version of this article was also published by Declassified Australia.