“I miss her so much – she was like a big sister to me,” reflects Esther Njoki, a wise 18 year old whose aunt Agnes Wanjiru was brutally murdered by a British soldier in 2012. Her body was found in a hotel septic tank months after she went missing.

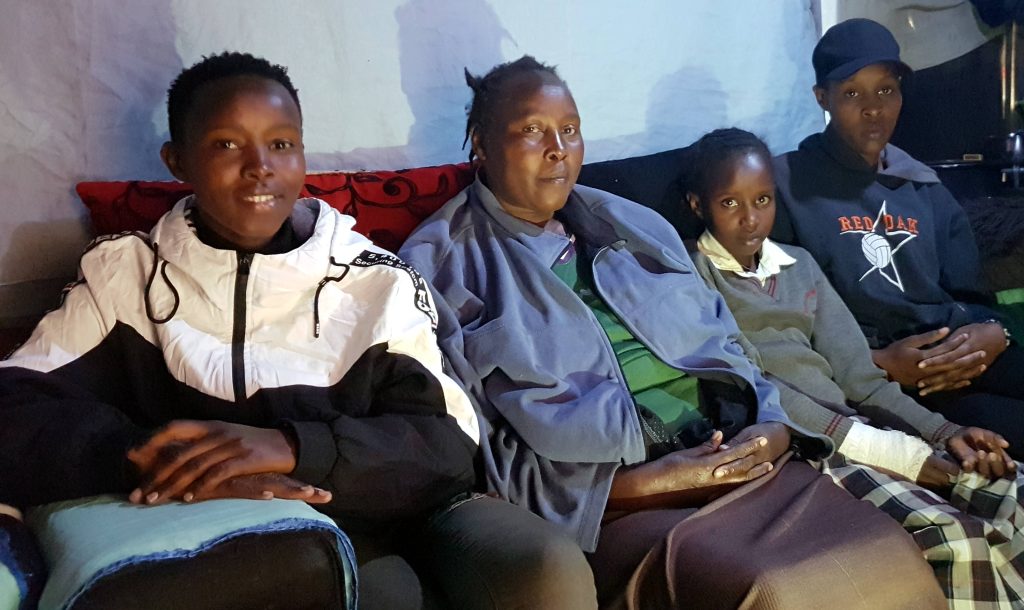

“There’s still no progress on extraditing her killer,” Esther complains, speaking to Declassified from Nanyuki, the garrison town near Mount Kenya where six of Wanjiru’s family live in a cramped room behind a teal painted kiosk.

“The UK government isn’t letting the soldier come here to face trial because they say Kenya’s prison conditions are too bad,” she reasons. “But I think it is fair for him to be imprisoned in Kenya.”

The family are squeezed on a sofa beneath a life-sized poster of Pope Francis, harshly illuminated by a fluorescent light bulb. Chickens chirp loudly outside and the smell of sewage sometimes invades the room.

Kenyan prison conditions are undoubtedly poor, but Wanjiru’s killer has left the victim’s family living in very basic circumstances. “It’s especially hard right now because our dad passed away two months ago,” Esther laments. “He was the breadwinner who was catering for us. So it is very sad.”

Wanjiru’s only child, Stacey, is now 11 and has spent almost her entire life without her mother. Against the odds, she is managing to do well at school. She enjoys maths and dreams of becoming a chef.

Last year the British public donated £9,000 to Stacey, but the funds are being held in a trust until she turns 18, so her living conditions are unlikely to improve soon. The money was raised amid outrage at revelations from an inquest that a UK soldier was behind her murder – and had openly joked about it on social media.

Yet in all the time that has passed since that wave of publicity, little progress has actually been made to bring Wanjiru’s killer to trial. Esther fears a £40m military co-operation agreement between London and Nairobi, which expired last year, might even be extended.

“The Kenyan government said that their contract would not be renewed until the case is over, but they’re still training here, so we are beginning to wonder,” she observes sharply. The treaty allows for around 3,000 soldiers to exercise in Kenya annually. It was rubber stamped in London this January by a House of Lords scrutiny committee, whose members included John Astor – a defence minister at the time of Wanjiru’s murder.

The committee did note “serious allegations of criminal activity levelled against some British soldiers in Kenya, including rape, sexual assault and even murder.” But they merely called on the UK government to “ensure that assistance is provided to the Kenyan authorities with any such investigations.”

Resistance to renewing the military deal is more pronounced among Kenyan politicians. The push back has forced Britain’s armed forces minister James Heappey to visit Nairobi twice since the Wanjiru scandal erupted.

The treaty was stalled at various political levels, until Heappey’s most recent trip last month broke the gridlock, even as he admitted on Kenyan TV that criminal investigations into the Wanjiru case have barely begun. “This really worries me because it’s a decade now and still justice has not been served,” Esther notes. “The UK government is dragging its feet. We want justice to prevail, especially for Stacey.”

When asked why the suspect had still not been extradited, a British Ministry of Defence (MOD) spokesman told Declassified: “The UK and Kenya are united in our efforts to get justice for Agnes. The jurisdiction for this investigation lies with the Kenyan Police Service. We continue to support the ongoing work between the UK Government and the Kenyan Government that will ensure the appropriate legal arrangements are in place.

“Both the Service Police and the Kenyan Police Service mutually share the intent to expeditiously progress this investigation and both parties remain engaged to achieve this. Details of any activity relating to an ongoing police investigation will not be disclosed to protect the independence of the investigation and the interest of justice.”

Brothel ban

It’s not just the defence deal that looks set to resume business as usual. Last month the hotel in Nanyuki where Wanjiru was murdered, Lion’s Court, reopened to customers after a long period of ‘renovations’. Its gaudy entrance gate, adorned with plaster statues of roaring animals, remains unchanged.

Next door is a much smarter residential compound, which a British officer rented out less than two years after the killing. The choice of location is somewhat macabre, given that Wanjiru’s murder was an open secret among soldiers.

These days, the British army is trying to distance itself from local institutions associated with violence against women. In July, the MOD passed a long-overdue policy, banning soldiers from paying for sex while stationed overseas.

It is a far cry from the bad old days in another country where the UK military trains – Belize. There, in the 1970s, British army doctors visited the city’s brothel twice a week to check women did not give troops sexually-transmitted infections.

“No way are they following that rule. Every night of every week they are going with girls”

The brothel ban, which outlaws “transactional sex”, is meant to prevent a repeat of what happened to Wanjiru, who was working as a prostitute at the time of her death. Yet few hotel or bar staff in Nanyuki had heard about the new policy when interviewed by Declassified on condition of anonymity.

One barman laughed: “No way are they following that rule. Every night of every week they are going with girls, especially in down town. You see them partying there with these call girls.” Another publican commented: “Nothing has changed. I’m sure they’re still paying women for sex, just now they might be more discreet.”

A hotel receptionist said: “I’ve not even heard of that policy. Mostly the soldiers just come to our restaurant for special occasions, but they do get rowdy, fight with each other and smash glasses. I think they go to other places for sex though.” Another source said a series of rented apartments in the town and near the army’s base were being used as brothels.

Many restaurants have varnished wooden plaques on their walls presented by visiting regiments that list the names of British soldiers who have enjoyed drinking there. Moran Lounge, a sprawling nightclub named after a Maasai warrior, has giant union jacks painted on the wall behind its pool tables.

As the night darkened at one bar, soldiers slammed down their glasses and gave an enthusiastic rendition of Sean Kingston’s Beautiful Girls, as local women danced suggestively. The men then departed, driving away in 4x4s with tinted windows.

While this might seem seedy, direct evidence of policy violations is more difficult to obtain. A woman who supports sex workers in Nanyuki admits: “It’s harder to know what’s going on now. The girls still have problems with clients, but many of them are afraid to talk to journalists or report it to the police.”

The woman, who asked not to be named, is dismissive of another post-Wanjiru initiative, which has seen the MOD fund a new sex crimes investigations unit of Kenya’s police. The British army’s local logo, of two crossed daggers on a red circle, sits awkwardly on the exterior of a cabin at Nanyuki police station.

“It’s like feeding a lion to a lion,” she said, arguing that Kenyan detectives won’t properly probe allegations against UK soldiers if their funding comes from the British army.

The Royal Military Police still seem to be doing plenty of their own inquiries. In the last five years in Kenya, the so-called Red Caps have received hundreds of misconduct complaints against British troops, of which 142 cases were investigated.

An army spokesman told Declassified that since the brothel ban came into force, “a very small number of incidents of Army personnel engaging in transactional sex in Kenya have been alleged and investigations are continuing.”

He added: “Our Zero Tolerance policies send a clear message that these types of behaviours are not permitted, and we continue to build on measures already introduced to tackle unacceptable sexual behaviours in the UK Armed Forces.”

This week, the MOD launched another special investigative unit, which could be partly in response to Wanjiru’s unsolved murder. The Defence Serious Crime Command will have “the jurisdiction to investigate the most serious crimes alleged to have been committed by persons subject to service law in both the UK and overseas…including rape and sexual assault.”

Whether it can crack this most controversial of cases remains to be seen.

Women’s refuge

Wanjiru’s family is not the first to fall foul of British soldiers and face a long wait for justice. A three hour drive to the north of Nanyuki is Umoja, a village where women have taken matters into their own hands.

“Umoja was established in 1990 after some of us were raped by British soldiers,” one of its inhabitants, Paulina Lekuireiya, tells Declassified. She is among 38 ladies from the brightly dressed Samburu nomadic group who live in this unique women’s only village.

“I was carrying things in the bush when five British soldiers found and raped me”

Sitting among their round huts, roofed with earth and black tarpaulins, three went on the record to allege sexual assaults by British troops. “I was carrying things in the bush when five British soldiers found and raped me,” Lucy Lesootia, one of the village’s founders, claimed. “After that my husband sent me away. I hate the British army. They should leave Kenya.”

Another resident, Rose Lakanta, said: “I’ve lived in Umoja village for 10 years. I feel safe from the British soldiers now. The British have done wrong things in this part of Kenya, especially to those who look after the cattle. The British raped us in the bush – some died, others became pregnant.

“Even those who don’t get pregnant, they have problems. If you’re on your own, and there are 10 of them, they will gang rape you. This causes health problems especially to the uterus and kidneys.”

Their allegations are just a handful of hundreds of rape claims made against British soldiers in Kenya since independence in 1963. An attempt by campaigners and lawyers to bring criminal charges collapsed in the early 2000s when a Royal Military Police review claimed some of the evidence had been fabricated.

Yet the village’s continued existence, just a five minute drive from a Kenyan army academy where British troops are stationed, is an open sore in the MOD’s attempts to improve its image in East Africa.

The appointment of two women to senior diplomatic positions in Kenya – as UK high commissioner and defence attaché – might allow an opportunity to start a healing process, but not one that has yet been taken. “The British ambassador has never come here to visit us,” Paulina notes bitterly.

Instead, the British army training unit in Kenya (known locally as Batuk), prefers to focus on its own community development schemes – which it parades on social media. In Dol Dol, a remote rural town between Nanyuki and Umoja, Batuk built a five metre long wooden footbridge across a ditch.

It was designed to stop local school girls having to enter a “deep gulley where predatory men could hide”. A bus was laid on so Kenyan journalists could cover the grand opening this April. By the time Declassified visited in November, the ‘gulley’ had dried out due to drought in northern Kenya, rendering the bridge pointless.

Esther, who inspected the bridge with Declassified, looked distinctly unimpressed. When told about Umoja village, she said: “It’s traumatising for those Samburu women as well as for us. It’s very traumatising.”

Back in Nanyuki, Esther intends to write a book about the town’s history of violence against women. The British army’s stay in Kenya will provide her with a rich and painful wellspring of material. In preparation, she reads The Fortune Men, a novel by British-Somali author Nadifa Mohamed. Shortlisted for the Booker Prize, it tackles institutional racism among UK police on a murder investigation – a plot Esther might find familiar.